Project Summary

Dilapidated infrastructure—especially the poor condition of roads, unreliable gas and electricity supply, and deteriorating municipal services—was consistently identified through the consultative process as a major impediment to economic growth in Georgia. The Regional Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project aimed to rehabilitate key regional infrastructure by improving transportation for regional trade, increasing the reliability of the energy supply, and improving municipal services in the regions outside of the capital of Tbilisi through three activities: Samtskhe-Javakheti Road Rehabilitation (SJRR) Activity, the Energy Rehabilitation Activity, and the Regional Infrastructure Development (RID) Activity.

Samtskhe-Javakheti Road Rehabilitation Activity

The SJRR Activity (original budget: $102.2 million; revised budget to $162.2 million with a final total disbursed: $212.8 million) targeted the rehabilitation of approximately 220 km (approx. 137 miles) of poorly maintained local roads into a key national and regional route, linking the capital of Tbilisi to an underserved agricultural corridor in Georgia’s southwest, as well as to Armenia and Turkey.[[The activity originally targeted the rehabilitation of 245 kms of poorly maintained roads. Several scope changes ultimately reduced the target to 220 km. The SJRR Activity also included construction or rehabilitation of 27 bridges along the route.]] At the time of compact development, the Samtskhe-Javakheti region was one of the poorer regions of Georgia, with a per capita income significantly below the national average and a high dependency on subsistence agriculture. In southern Georgia, deterioration of the roads had cut the region of Samtskhe-Javakheti off from the rest of the country. With high costs to transport produce out of the region, local farmers were unable to compete with farmers elsewhere. Moreover, the poor road infrastructure also created significant obstacles to importing agricultural inputs and other goods. Rehabilitation of roads in the Samtskhe-Javakheti area was thus expected to foster economic development in the region.

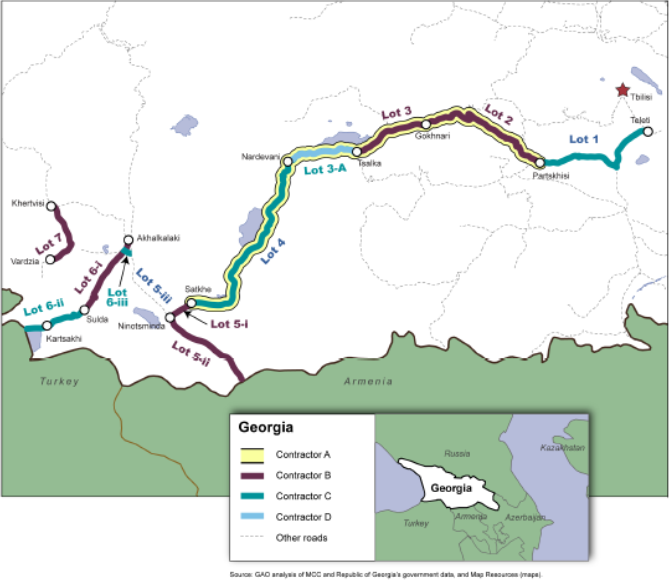

Although successfully completed by the end of the compact, the SJRR Activity proved to be challenging. In April 2007, MCG sought to procure contractors for three lots, each 75 to 80 km (46 – 50 miles) in length. However, the prices quoted exceeded the amount of funding available. As a result, MCG decreased scope, revised the activity into smaller sections, conducted a new procurement, and awarded four total lots to two contractors between March and May 2008.

In November 2008, MCC added $100 million to the compact budget—increasing the funds available through the Georgia Compact to $395.3 million several months after the Russia-Georgia conflict. This increase was part of an overall United States Government effort to support Georgia. It allowed MCG to complete the Samtskhe-Javakheti Road Rehabilitation Activity as originally planned, covering the additional costs resulting from the global rise in oil and construction prices, as well as road engineering design changes. As a result, the scope of the SJRR Activity was increased back to 220 km and MCG awarded three more contracts for the remaining lots.

MCG SJRR Activity by Lot

Meanwhile, one of the originally selected construction contractors performed poorly, jeopardizing timely completion of over half the road. As a result, certain sections of the road were removed from the contract and awarded to other contractors in 2009. Due to continued poor performance of that same contractor, MCA-Georgia ultimately terminated the contract in August 2010. All remaining roadwork was re-bid to companies committed to completing the work within MCC’s five-year timeline. By the end of the compact term 220 km (136 miles) of rural roads were rehabilitated, connecting this isolated region of Georgia to the capital, and facilitating access to international trade with Armenia and Turkey. Although work was completed on all road segments prior to the compact end date, the combination of rushing to complete and working in less-than-ideal weather conditions meant that, in some places, the quality of construction suffered.

Additionally, this project used newly integrated, European design standards, instead of previous former Soviet Union (FSU) standards, for the road rehabilitation. Historically, road design standards in Georgia were those used throughout the FSU and had not been updated since 1984. The FSU standard was not in keeping with modern developments and practices; for example, it gave less consideration to an economic justification, proper drainage, traffic safety, and continuity of road design. The shortcomings of that approach were apparent based on a review of the condition of the project roads in need of rehabilitation.

Prior to the commencement of the SJRR Activity, the Georgian roads agency, with assistance from the World Bank, took the first steps toward introducing modern European practice for technical standards and pavement specifications in Georgia. They settled on the British standard, incorporating newly harmonized EU standards and combining the latest developments in design policies with economic considerations. As a condition precedent for disbursement of the roads activity, the GoG committed to annual increases in state road maintenance to ensure the sustainability of the investment. Georgia fulfilled this commitment, increasing the budget from $33.6 million in 2006 to over $56 million by 2010.

Energy Rehabilitation Activity

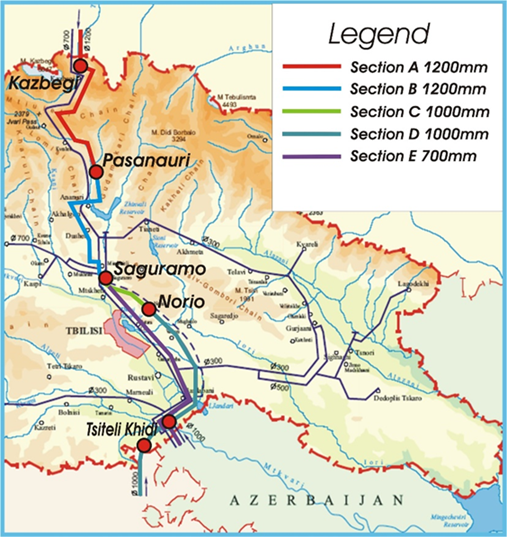

The Energy Rehabilitation Activity (original budget: $49.5 million; revised to $62.5 million; with a final total disbursed: $45.8 million) aimed to increase energy reliability and security and reduce energy losses throughout Georgia by rehabilitating sections of the North-South gas pipeline system. At the time, that system was the country’s primary pipeline for natural gas running from Russia in the north to Armenia, south of the country. Following the break-up of the Soviet Union and with the decline of the Georgian economy, the pipeline was neglected and required a comprehensive rehabilitation program. Under the Energy Rehabilitation Activity, the Georgian Oil and Gas Corporation (GOGC) was designated by MCG as the implementing partner for the project. GOGC was responsible for preparing project designs, environmental assessments, and the technical specifications needed for equipment procurement. The GOGC was responsible for obtaining necessary environmental and construction permits, overseeing land acquisitions, supervising construction and monitoring the progress of the project.

MCG Gas Energy Rehabilitation Project

In July 2006, in partnership with the energy company British Petroleum (BP)[[BP had recently completed construction of an oil pipeline across Georgia as part of the Baku/Tbilisi/Ceyan pipeline project from Azerbaijan to Turkey.]] and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), MCG and GOGC oversaw the selection of qualified contractors. In December 2006 and January 2007, two contractors were selected and to undertake the three phases of construction: six sites in 2007 (Phase I), nine sites in 2008 (Phase II), and an additional seven sites in 2009 (Phase III). This phased approach allowed GOGC to assume an increasing level of responsibility with each phase, emerging stronger and more capable of managing the pipeline. By the conclusion of the compact, 22 key sections of the main natural gas trans-shipment pipeline were rehabilitated - replacing damaged pipe at river crossings, in landslide areas, on heavily eroded slopes, and with exposed heavily corroded pipe. In addition, several valves were replaced.

Regional Infrastructure Development Activity

The RID Activity (original budget: $60 million; revised to $86.0 million; with a final total disbursed of $51.1 million) was designed to reduce the costs and burdens associated with intermittent, unreliable public utilities. By strengthening the capabilities of ministries and sub-national governmental jurisdictions to plan, develop, fund, construct, and operate regional and municipal projects.[[The World Bank funded the Municipal Development and Decentralization First Project under which 89 investment projects in municipal infrastructure were implemented in Georgia between 1997 and 2002. From 2003 to 2007, investments and technical assistance were provided to more than 20 local self-governmental bodies within the Municipal Development and Decentralization Second Project, also funded by the World Bank.]] The activity provided grants to eligible government entities (local self-government, municipal enterprise, and central government) for the development and financing of infrastructure projects, such as:

- Investment projects for the purchase of machinery/equipment.

- Development projects that cover needed due diligence, such as feasibility studies, environmental studies, and preparation of designs.

- Technical assistance projects that trained and built the knowledge of eligible municipal entities through staff support or training.

MCG had not identified specific projects to be funded at the time the compact entered into force; however, certain parameters for the grants were defined in the compact, and RID projects included: investments in the water supply, sanitation, irrigation, gasification, local roads, and solid waste sectors. Projects, once identified by an eligible governmental entity, had to demonstrate the following: a contribution to economic and social development of the region(s), achieve an economic rate of return above an agreed threshold, be supported by an operations and maintenance plan and budget for a period of at least five years after completion, comply with MCC’s Environmental Guidelines, and meet the requirements of an Operations Manual satisfactory to MCC. The size of individual grants was originally planned to vary between $500,000 to $7 million; however, in August 2007, with MCC’s approval, the funding limitations were removed to ensure efficient implementation of the projects.

After the compact entered into force, review of RID proposals, and extensive consultations with the GoG, it was decided that water and sanitation were the key sectors for RID’s investments. Georgia’s water and waste-water systems were in a particularly severe state of disrepair. In many regional cities of Georgia, communities only received water for two-three hours a day with minimal water pressure. Many in the population had to pump water into individual reservoirs to stock a day’s supply. From the proposals, five municipal water supply and wastewater collection projects were selected for implementation, based on the needs, projected economic impact, and implementation timeline.

The Municipal Development Fund (MDF), a Georgian government entity which had served as the program implementation unit for the above-referenced World Bank municipal development program, was designated as the RID Activity implementer under a Collaboration Agreement entered into with MCG in 2006.[[Later, during the term of the compact, the MDF was designated by the GoG to serve as the preferred vehicle for implementation of all donor-funded municipal infrastructure and social investments.]]

In determining how best to execute the portfolio of RID projects, MCC sought efficiencies. First, MCG elected not to fund new feasibility studies or engineering designs for investment sub-projects. Given the five-year timeframe of the compact and its objective to leverage its funds, MCG selected projects already conceived and designed by the European Union, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency.

Second, to leverage compact funds, MCC and MCG often financed projects in parallel with other institutions such as EBRD. With prior MCC approval, MCG entered into parallel financing agreements with the EBRD for three municipal water supply projects. Based on the procurement plans for these three sub-projects, MCG contributed roughly 50 percent of the total combined costs, thereby benefiting from leveraging donor and GoG contributions.

Lastly, rather than duplicating what was already in place, MCC and MCG contracted for oversight with organizations best suited to the task. The RID Activity was unique for the extent of cooperation among MCG and other international donor organizations. RID Activity implementation differed from the standard compact implementation and oversight model in that MCG entered into a service agreement with the World Bank. The World Bank monitored the MDF’s compliance based on the Operation Guidelines (approved by MCC), reviewed, and issued approvals to all steps of the procurements on certain RID projects, and monitored adherence to MCC Environmental Guidelines. For those projects jointly funded with EBRD, EBRD reviewed and approved the projects’ procurements and compliance with its environmental guidelines. Although based on the procedures of the World Bank and the EBRD, procurements were conducted in substantially the same manner as those conducted in accordance with the MCC Program Procurement Guidelines. And, at all times, MCC retained its rights of oversight, inspection, and audit.

The main projects funded under the RID Activity were the Poti, Kutaisi, Kobuleti, Borjomi, and Bakuriani municipal water supply and wastewater collection projects, plus a number of studies and designs for other projects that could be funded by other donors.

MCG RID Sub-Project Sites

The water and sanitation projects solved some critical infrastructure needs in all project cities, and generally advanced each city’s water supply and wastewater management. The RID projects generally helped to reduce electrical consumption in their respective cities through improved well pumping and pump station system improvements. The RID Activity achieved 24-hour water supply in three out of the five cities. These three cities—Kobuleti, Borjomi and Bakuriani—were the main tourist destination cities in Georgia, and tourism was a fast-growing sector of the economy in Georgia. Implementers cited that RID projects in these cities improved conditions for the development of tourism and small and medium-sized businesses, which they hoped would lead to income generation, reduced costs, and improved living standards. Reduced risk of water-borne diseases was also an outcome expected by implementers and residents, as new water treatment plants were installed in Borjomi and Bakuriani, and water treatment plants were significantly improved in Kobuleti. As part of the water systems rehabilitation, the RID Activity also provided technical assistance to improve water utility management, operations, and maintenance to water companies and municipalities.

Ultimately, the RID Activity encountered difficulties in implementation. The activity undertook municipal water projects in a sector that had been long neglected, and the original expectations of what could be accomplished with the existing budget and within the available timeframe were set too high. In two of the five cities (Poti and Kutaisi) where the activity funded investments, sub-standard designs required multiple revisions, and extra efforts were needed to help ensure that the works were completed on time. It also became obvious that it was impossible to achieve the original goal of 24-hour water supply throughout these two cities due to budget constraints and the amount of work for full rehabilitation. In Kutaisi, water supply and delivery improved and some cost efficiency was achieved, as the pumping systems were replaced. However, 24-hour water supply and full rehabilitation was done in only the most impoverished part of the city, and most of the city did not achieve continuous 18-hour supply. In Poti, the project failed to increase water supply significantly and only improved distribution on a small number of streets.

After the compact ended, the GoG continued investing in Kutaisi water supply systems through support from the Asian Development Bank. The GoG decided to consolidate the fragmented municipal water supply into a new United Water Supply Company of Georgia LLC established in 2009-2010. Under a $500 million Asian Development Bank commitment in 2011 for the water sector, the United Water Supply Company of Georgia LLC (UWSCG) worked to optimize the investments within the long-term needs of the cities[[For a description of the ADB funding for follow-on water and sanitation projects, refer, among other documents, to: Asian Development Bank; Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors; Proposed Multitranche Financing Facility: Georgia: Urban Services Improvement Investment Program; Project Number: 43405; March 2011. Asian Development Bank; Urban Services Improvement Investment Program (RRP GEO 43405): Development Coordination. This document cites Millennium Challenge Georgia’s activities targeted at improving water supply and sanitation infrastructure in the major cities.]]. With a more holistic approach in mind, the UWSCG decided that a large block of funding for city water/sewerage problems would be better than the piecemeal approach adopted in the past. Additionally, given the environment of constrained financing, the UWSCG continues to extend water services to more cities throughout Georgia with funds received from other donors.

Project Economic Analysis

- $310 700,000 millionCompact Project Amount (including amendment)

- $309,899,714.29Total Disbursed

Estimated benefits correspond to $309.9 million of project funds, where cost-benefit analysis was conducted:

- Estimated beneficiaries at compact close: 4,591,582

- Estimated net benefits at compact close: -$646,253

Estimated Economic Rate of Return:

At the time of compact signing, economic rates of return (ERRs) were calculated for the SJRR Activity, the Energy Rehabilitation Activity, and the RID Activity. Estimated benefits at the time of signing come from original ERRs and correspond to the original $211.7 million of project funds, where cost-benefit analysis was conducted. All three activity-level ERRs were updated at compact closure.

| Estimated Economic Rate of Return | Estimated Beneficiaries | Estimated Net Benefits[[Net benefits refer to discounted benefits minus discounted costs at a 10% discount rate.]] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samtskhe-Javakheti Road Rehabilitation Activity(over 24 years) | At the time of signing | 20% | 58,079 | $65,592,969 |

| At compact closure | 15% | 58,079 | $55,771,982 | |

| Energy Rehabilitation Activity | At the time of signing (over 10 years) | 11.7% | 4,591,586 | $2,641,184 |

| At compact closure (over 45 years) | 7.7% | Not estimated | -$9,560,406 | |

| Regional Infrastructure Development Activity | At the time of signing (over 19 years) | 12% | 263,950 | $13,273,989 |

| At compact closure (over 25 years) | 0.7% | 67,865 | -$46,857,829 |

Key Performance Indicators and Outputs at compact end date

| Indicators | Baseline (2006) | Actual Achieved (2011) | End of Compact Target (2011) | Percent Complete[[Formula for Percent Complete: (Actual-Baseline)/(Target-Baseline)*100]] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samtskhe-Javakheti Road Rehabilitation Activity | ||||

| Savings in vehicle operating costs | 0 | 13,770,000 | 13,117,000 | 105% |

| International Roughness Index[[International Roughness Index (IRI): Roughness is a measure of the irregularity of the road surface. It affects the operation of a vehicle (safety, comfort, and speed of travel) and costs of operation through vehicle wear, fuel consumption and the value of human and asset time spent in transit. This affects the economic evaluation of proposed road maintenance and upgrading expenditures. The lower the number, the smoother the road.]] | 16.6 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 107% |

| Annual Average Daily Traffic (Vehicle) | 612 | 1,092 | 1,183 | 84% |

| Travel Time (Hour and minute) | 8:13 | 2:42 | 2:45 | 101% |

| Kilometers of roads completed | 0 | 220 | 220 | 100% |

| Energy Rehabilitation Activity | ||||

| Sites Rehabilitated (Phases I, II, III) | 0 | 22 | 22 | 100% |

| Percentage of Construction Works Completed (Phase II) | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100% |

| Collection Rate[[Collection rate is defined as the percentage of sales by GOGC collected for all services provided in the form of cash payments, (which cash receipts may include proceeds from the sale of gas taken as payment in kind for transmission services).]] | 47% | 113% | 95% | 119%[[It was possible to achieve a fee collection rate above 100% through collection of arrears in the year in which this measurement was taken.]] |

| Regional Infrastructure Development Activity | ||||

| Population Served by all RID sub-activities[[Estimated number of residents of Poti, Kutaisi, Kobuleti, Borjomi, and Bakuriani, whose potable water supply increased to 18 hours per day.]] | 0 | 67,865 | 265,964 | 26% |

Explanation of Results

As mentioned above, RID projects were identified through public consultations after compact signature. MCG conducted due diligence based on existing feasibility studies and designs developed in the investment proposals for each city which were individually approved by MCC. These investment proposals, as well as initial calculations on the number of people benefiting from the program and ERR estimations, projected 24-hour water supply to nearly the whole population of these five cities. The biggest contributor to beneficiary numbers was Kutaisi, the second largest city by population in the country at that time. After engineering designs were finalized, it became obvious that full rehabilitation of Kutaisi water supply system was not possible, so the project focused only on one neighborhood, which received 24-hour water supply by the end of the compact. The project also rehabilitated the central reservoir and replaced all old Soviet-style pumps with new, energy efficient ones in Kutaisi. This improved the water supply for the whole city, however the indicator for “Population Served by all RID subprojects” only counted those residents that received 24-hour water supply as originally planned, which was only the subsection of the city. In addition, due to the inefficiencies of Poti project designs, the project in Poti did not reach the intended number of Poti residents. Hence, there is a reduction in both population reached as well as household savings. Ultimately, the RID subprojects served 67,865 residents of the five cities, 26 percent of the target.

Evaluation Findings

Under the Regional Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project, two evaluations were conducted: one that measured the impact of the SJRR Activity, and the other independently conducted an endline cost-benefit analysis of the Energy Rehabilitation Activity. The planned Regional Infrastructure Development Activity evaluation was cancelled due to feasibility challenges.

Samtskhe-Javakheti Road Rehabilitation Activity

MCC commissioned an independent impact evaluation for the Road Rehabilitation Activity and the full results and learning can be found on the evaluation catalog and summarized in the Evaluation Brief. The evaluation was designed to answer the following high-level question about the activity: How does the road rehabilitation effect/cause economic development, new businesses, and economic and social integration in the region?

In addition, the following categories of outcomes were explored by the evaluation:

- Transportation related outcomes: traffic counts, vehicle speeds, travel times, and availability of public transport;

- Investment, land use, and employment: industrial investment, land uses, cropping patterns, and employment;

- Market prices: the prices of basic commodities on the local market;

- Household welfare: income, consumption, and asset ownership; and

- Access to health and education: utilization of health care and education services.

Key Findings include:

Travel and Transport

- Rehabilitating the Samtskhe-Javakheti road successfully improved travel conditions. Traffic volume and average speed increased, and travel times to both the capital city of Tbilisi and local markets decreased.

Industrial Investment, Land Use, and Employment

- The improved roads significantly increased industrial investment in nearby communities.

- There were no observable changes in cropping patterns or agriculture land use at the community level.

Market Prices

- Local prices of commodities were affected by the improved roads, but in ways that were difficult to interpret in relation to the program’s objectives.

Household Welfare

- The evaluation did not find that the improved roads impacted income, consumption, asset ownership, employment, or utilization of health and education services at the household level. However, the timing of the evaluation, which was less than two years after the project concluded, limited its ability to assess impacts on household welfare.

MCC Learning from this evaluation

- Base evaluation decisions on a clear program logic. The decision of when and what data should be collected should be driven by a clear program logic that underlies the investment decision.

- Set realistic time horizons and keep data collection plans flexible. From the beginning, implementers and evaluators should build actions to mitigate risks associated with project delays into the evaluation design.

- Ensure sufficient statistical power to measure realistic changes in key outcomes.

- Include an upfront national or area-wide road network analysis based on selected criteria such as traffic volume, roughness index, and other parameters in the roads project selection process, as noted in the Principles into Practice: Lessons from MCC’s Investment in Roads.

- Comprehensively address policy and institutional constraints to road maintenance and seek assurances from the partner government that the necessary mechanisms to ensure sustainability are in place prior to MCC’s investment.

Energy Rehabilitation Activity

An independent cost-benefit analysis of the Energy Rehabilitation Activity, which can be found in the evaluation catalog, was completed at compact closeout. The analysis aimed to independently assess the Energy Rehabilitation Activity’s ERR after the compact ended. Prior to compact start, the ERR was estimated to be 11.7 percent. The post-compact, independent analysis revised the ERR downward to 7.7 percent.[[The ERR estimate would increase to 9.2% if the model instead assumed an emergency repair cost premium of 100%, rather than 50%.]] The decrease was largely due to the arrival of alternative gas sources from Azerbaijan and Georgia’s reduced dependence on Russian gas.

Regional Infrastructure Development Activity

The RID Activity was the subject of an independent impact evaluation, which was later cancelled. Completed evaluation materials can be found in the evaluation catalog, along with a memo describing cancellation of the evaluation’s third and final phase. MCC canceled the evaluation in part because the evaluation methodology and data collection methods were unlikely to credibly measure project outcomes, and in part due to changes in project design throughout the compact. No further external evaluation is expected for the RID Activity.