Introduction

MCC is required by its statutory regulations to conduct cost benefit analysis (CBA) and to calculate the economic rate of return (ERR) on projects supported through country compacts. ERRs form a critical part of the project approval process and are required to equal or exceed a threshold level of ten percent over the medium term. To clarify methodology and to improve the consistency across country compacts, the division responsible for estimating ERRs is developing a series of reports outlining methodology for each major investment sector. This report covers Land and Property Rights (LPR) projects. The guidelines aim to help MCC economists better understand the methodological tools available, and to provide greater methodological clarity to external practitioners. This should help to provide more consistent application of CBA methodology.[[This is a ‘living document’. As methods improve and new insights develop in the relevant literature, MCC’s approach also aims to evolve and to keep pace. MCC staff will periodically update the guidelines to reflect advances in economic theory and practice, and to provide tools to analyze new LPR investment types as they are encountered.]]The first section of the document reviews the theory and evidence on benefits of LPR investments. Section 2 provides a typology of LPR interventions and associated benefit streams to serve as a starting point for economic analysis. Section 3 presents principles to guide the modeling of LPR investment economic returns.

Modelling Economic Benefits: Theory and Evidence

LPR investments can increase income primarily through five mechanisms. First, land[[As used in this paper, the term “land” refers to land and all related property and natural resources associated with that land (e.g., water, forests and minerals).]] users are more likely to make welfare-enhancing land-attached investments when they are confident that they can reap the full social return of these investments. Increased perception of tenure security through improvement in land governance, land tenure status, land user knowledge and beliefs, and related legal resources[[Land governance concerns “the rules, processes and structure through which decisions are made about access to land and its use, the manner in which the decisions are implemented and enforced, and the way that competing interests in land are managed” (Palmer, Fricska and Wehrmann, 2009). Land tenure status refers to the particular property right type held by individuals and by groups within this governance system. This can include freehold right, use right (e.g. leasehold tenures), bundles of rights to common resources, or other right types, any of which may be limited in a variety of ways.]] can therefore result in an investment level closer to the social optimum (i.e. the level at which the marginal social cost of land investment is equal to the expected net present value (NPV) of its social return).[[Removal of regulations (e.g. building height restrictions) that suppress investment can have the same effect—although negative externalities must be carefully considered.]]Second, individuals and firms are more likely to buy-in or rent-out a parcel of land if they are certain to maintain the tenure right to that parcel after doing so (transferability).[[Referred to as alienation rights in property law.]] This can ensure that parcels are allocated to the individuals and firms that have a comparative advantage in their use,[[Including execution of land-attached investments to develop those parcels.]] while allowing others to monetize parcels to which they have rights and engage in other activities in which they are more productive. For instance, transfers can give land access to those farmers with a comparative advantage in cultivation while freeing others with land rights to engage in non-farm enterprise work in which they are more productive or to migrate to urban areas.

Third, it has been argued by De Soto (2000) that more secure and formal tenure rights to a parcel of land will increase the willingness of banks to accept that parcel as collateral for a loan, thereby increasing its owners’ access to credit. This credit can be used to finance investments whose returns exceed the cost to banks of providing those loans. In practice, these credit effects have often not been observed.[[Sanjak 2012; Lawry et al, 2014; Higgins et al, 2017.]]

As discussed below, the willingness of banks to accept land as collateral for a loan also depends on creditworthiness (bankability) of the potential loan recipient, value of the parcel to the bank in foreclosure, and a variety of characteristics of the legal and financial environment. Unless there is compelling contextual evidence in support of a credit effect, it is therefore recommended that credit effects be excluded from the ex-ante ERR of LPR investments.[[Credit effects are more likely in contexts where beneficiary incomes are higher, plots are larger and/or located in urban areas (and so constitute an asset of value to lenders), contract enforcement mechanisms are strong, and the financial sector is well developed. Even in cases where evidence of a potential credit effect is insufficient for inclusion in ex-ante CBA, ex post evaluation tests for a LPR credit effect may be of interest where the effect is believed plausible.]]

Fourth, LPR investments may reduce the cost of land administration service delivery.[[The FAO defines land administration as “the way in which the rules of land tenure are applied and made operational. Land administration, whether formal or informal, comprises an extensive range of systems and processes to administer, including Land rights: the allocation of rights in land; the delimitation of boundaries of parcels for which the rights are allocated; the transfer from one party to another through sale, lease, loan, gift or inheritance; and the adjudication of doubts and conflicts regarding rights and parcel boundaries; Land-use regulation: land-use planning and enforcement and the adjudication of land use conflicts; and Land valuation and taxation: the gathering of revenues through forms of land valuation and taxation, and the adjudication of land valuation and taxation disputes.” (FAO 2002).]] This would include benefits such as reduction in the average cost of registering, mapping and transferring parcels and resolving land conflicts, as well as reduction in time and travel cost incurred by service users. For example, if a LPR activity results in access to land administration services at the district rather than national level, the resulting reduction in user time and travel expense would be an economic benefit. In some cases, the reduction in the cost of land administration services may be large enough to have a meaningful price effect on land registrations and transfers as well, resulting in additional benefits through mechanisms one and two above.

Fifth, LPR investments may redefine the allowed uses of land in ways that reduce the cost of non-land public service delivery (e.g. water and wastewater, electricity, and road infrastructure and public transport), negative externalities from colocation of incompatible uses (e.g. excessive noise or poor air quality proximate to residential areas), or negative externalities from inappropriate uses (e.g. pollution, degradation of common land through overgrazing). For example, an investment that establishes an optimal network of public roadways in an underdeveloped area would reduce the future cost of delivering public services to this area.

The observable benefit streams through which the above five mechanisms increase incomes are effects on the productivity or value of land assets,[[Since all future income streams from an asset should be reflected in its price (Rosen 1974), the inclusion of both land productivity and value of land as beneficiary streams would double count project benefits. Use of land productivity is generally favored for rural areas, while value of land is often favored for urban areas, for reasons discussed in section III.]] and net reduction in the cost of public service delivery.[[In contexts where users are not charged the full cost of public service delivery, reduction in service delivery cost may not be fully reflected in land productivity or values.]] [[Effects on non-land attached investments or labor activities resulting from increased credit access, ability of households to transfer land to other parties, or reduced land guarding (Field, 2005)—including reduced guarding impacts occurring through increased rural-urban migration (Field, 2005; Deininger et al. 2013; de Janvry et al. 2017)—may also be incorporated where there is evidence that they are substantial.]] [[Availability of accurate land ownership records also has potential to enable enforcement of rules (through penalties or subsidies) that require land owners to contribute to the provision of public goods—for example, connection to water infrastructure, or discouragement of electricity theft. A key example is the implementation of property tax collection, through which LPR investments have potential to reduce the cost and overall distortionary impact of municipal revenue mobilization (Ali et al. 2018). Property taxes are relatively fair and progressive as most benefits of municipal services are capitalized in land values (Collier et al, 2017). Effects on rule enforcement and revenue mobilization may also be included where there is evidence that they are substantial. Guidance on the CBA of revenue mobilization investments, however, is outside the scope of this document.]] Both the measurement of these outcomes and estimation of LPR investment impacts on them are fraught with challenges, reviewed in detail in section III. Nonetheless, a vast literature examines the impact of LPR investments.[[See Feder and Feeny 1991; Besley 1995; Lawry et al 2014; Gignoux, Macours, and Wren-Lewis 2014; and Higgins et al 2017. While the literature is extensive, LPR evaluations have focused on tenure formalization effects, and few have used rigorous experimental designs. For internal users, the literature cited in this document is available in MCC EA’s Land Literature Library, located on the share drive here.]] Part I.1 reviews cross-cutting issues that emerge from this literature, while sections I.2 through I.6 review the most important evidence on LPR effects through the above five mechanisms.

Cross-Cutting Issues

The Importance of Context

LPR investment impacts are highly context sensitive. Land rights formalization is unlikely to increase perceived tenure security, for example, in areas where land use rights are already perceived to be secure.[[Both impacts on land-attached investment and returns to increases in land-attached investment are likely to be higher in areas with poor baseline tenure security. In fact, high returns to investment in land attached vs moveable assets is a signal of tenure insecurity. For example, Deininger and Chamorro (2004) find that the return to land-attached investments in Nicaragua during a period of land tenure regularization following high tenure insecurity was 29%, versus a return of 12% to livestock and 3% to machinery investments.]] Likewise, in many contexts, strengthening and legally recognizing customary or informal rights systems (or providing intermediate rights, such as long term leases)[[In many contexts all land is formally owned by the state, but long-term lease documentation serves as an effective title (e.g. 99-year leases in the case of Zambia) that provide sufficient tenure security.]] would be substantially more cost-effective at increasing perceived tenure security than formalization via full private/freehold title.[[Lawry et al, 2014.]] In other contexts, the greater expense required to establish stronger legal rights may be justified by interest from outside investors in entering an area or to allow use of complex contractual structures to facilitate mortgage lending or assembly of land for condominiums (in urban areas).[[Regardless of the legal strength of the right established, credibility, specificity and transparency both to the community and to outsiders through documentation or other means are key.]]The presence of complementary inputs is also critical to LPR impact. Effects of improved tenure security perception on investment and transfers is determined in part by land users’ access to input and output markets, credit access, and household assets. Credit constrained households, for example, may increase land-attached investment in response to improved tenure security while also reducing other household investments.[[Lanjouw and Levy, 2004 (page 906 and 930).]] For this reason, LPR activities are sometimes implemented in concert with a broader package of agrarian or other market reforms.[[Castaneda and Pfutze, 2013.]] Contextual heterogeneity in potential impact is an important consideration in both designing and geographically targeting LPR investments.

In a systemic review of 20 quantitative and qualitative studies, gains in land productivity were shown to be significantly higher in South America and Asia and in “wealthier settings” than in Sub-Saharan Africa. It is unclear whether this is due to what authors call a “wealth effect,” in which lower levels of wealth can explain lower levels of investment and productivity, or an “Africa effect,” in which the efficiency of pre-existing customary land tenure systems are underestimated by researchers, thereby causing them to overestimate potential returns. In other words, “insecurity is not present to the degree by which researchers estimate,” so the differential between pre-reform security and post-reform security tends to be lower than anticipated. Customary land tenure systems are diverse, but in many cases confer rights that are held for life, inheritable, and considered a social right.[[Lawry et al, 2014 (page 42 and 59).]]

Likewise, within a given context, LPR investment effects on economic outcomes are likely to be highest for sub-groups with lower baseline tenure security. For example, the positive effect of land tenure rights on investment in soil conservation for women was found to be double that for men in Rwanda. Likewise, the effect of land titles on investment in conservation in Vietnam was also highest among landholders that faced greater threat of land reallocation. In areas that lacked a threat of land reallocation, there was no difference in investment among those with land titles and those without.[[Ali et al, 2014; Saint-Macary et al, 2010.]]

Sustainable LPR investment impacts are contingent on both investment design quality and design compatibility with the characteristics of the local context. An analysis on the effects of land titling on agricultural productivity in Madagascar, for example, found no relationship: After their initial establishment, titles were rarely updated due to the prohibitive time and financial cost of doing so when land was traded, passed down, or divided into smaller parcels.[[Bellemare 2013. Similar issues were encountered in Mongolia prior to MCC’s first compact there. In Burkina Faso, MCC is evaluating the degree to which local institutions are operating and the demand for new registrations or transfers of land rights certificates.]] As a result, formal titles no longer reflected current rights and the system fell into disuse. Likewise, a recent analysis of the sustainability of Rwanda’s land registry following a nation-wide program of first-time land tenure regularization emphasized the importance of planning the registry set-up and operations phases jointly with a clear analysis of the social benefits, private benefits to each user type, and potential matches between these and financing options.[[Ali, Deininger and Duponchel 2017]]

In many contexts, incorporating public awareness campaigns may increase or even be necessary to achieve any LPR investment impact. Following the initiation of land rights reform in Uganda, for example, researchers found that households with greater knowledge of their newly acquired rights had up to 20% higher agricultural output and 25% higher land values.[[Deininger and Castagnini, 2006.]] Moreover, awareness campaigns may disproportionately benefit the disenfranchised. In Benin, female-headed households were less likely than male-headed households to be aware of land tenure reform activity, and also less likely to take part in meetings on rural land use plans.[[Goldstein et al, 2015 (page 21). However, it is unclear whether this is due to poor engagement with female headed households or lower interest from female participants, given that the project formalized customary tenure rights which women are less likely to hold.]] Awareness raising and related trainings are equally key for government and local officials who may be unaware of the details of newly passed legislation or new systems and procedures. Often de jure legal reforms are not implemented due to lack of awareness, financial resources or capacity.

Overall, the findings highlight the importance of the institutional, economic and political context in which reforms will be implemented to achieving desired outcomes. As noted by Lawry et al. (2014), land tenure programs cannot be “effectively implemented unless they are fully embraced by national governments, cognizant of the political costs and benefits to implementation, and prepared to bear the high fiscal costs of implementation.”[[Lawry et al, 2014 (page 62). Exceptions include India and Mexico where individual states governments have authority over land governance and have implemented reforms.]] Moreover, sufficient resources and user demand must be in place to maintain land administration systems once they are established. Key national and sub-national moderating factors to consider include governance, social norms and practices, land use, and markets.[[Ibid (page 18).]]

Potential for Unintended Consequences

Tenure formalization investments designed without proper understanding and recognition of existing customary or informal primary and secondary land use rights can result in competing claims on plots that reduce tenure security, or outright loss of use rights for particular sub-groups.[[Castaneda and Pfutze, 2013. “Customary,” as defined by USAID is “traditional authority,” or “communities as a whole,” depending on country context (Stickler and Huntington, 2015).]] In Sub-Saharan African countries with pre-existing customary land tenure systems, conversion of these systems to European-style land rights systems have “rarely occurred historically without considerable social and economic displacement.” In these cases, much of the fear of displacement is fear of the state rather than individuals.[[Lawry et al, 2014 (page 12 and 53).]]This risk is especially high for women and marginalized groups. Women often hold property rights via intermediary men, who have more power to enforce those rights. Poorly structured LPR reforms may not only be insufficient in redistributing wealth to the poor, but can actually deepen inequalities.[[Goldstein et al, 2015 (page 6); Smith 2004; USAID, 2007 (page 13).]] In Kenya, it was found that while land tenure reforms created a land-holding class, it also created a landless one, namely secondary rights holders such as women. Authors of this systematic review stress the importance of studying customary land tenure systems, and note that Mozambique, Kenya, and South Sudan stand out as “pioneering” the statutory recognition of community-based land rights.[[Lawry et al, 2014 (page 61). Other examples include Madagascar, Benin, Burkina Faso, and Angola.]] Likewise, a well-intentioned pilot LPR project in Rwanda increased the tenure security of married women, but inadvertently reduced the tenure security of unmarried women.[[Ali, Deininger, and Goldstein 2014. Reforms were made to remedy the issue based this analysis.]] Where statutory recognition is given to customary or communal land administration systems, it may be possible to reduce potentially negative distributional effects through reforms that make traditional land authorities accountable to public oversight, or reassign their responsibilities to civil land boards.

Likewise, the rights of pastoralists must be identified and incorporated into LPR program design and implementation to avoid unintentional marginalization and increases in conflict between pastoralists and sedentary farmers. Because pastoralists may not be members of the local community and may not be present at the time of participatory land use planning exercises, there is a risk that their rights are not be documented and protected. In Niger, for example, MCC staff have found that land right conflicts between nomadic pastoralist and sedentary farmers are quite common.

Fortunately, when carefully structured to mitigate risks to sub-groups, LPR investments have potential for very positive distributional effects. The poor have more to gain from LPR reform, since informal rights tend to be weaker for those low in the political hierarchy, which disproportionately includes women and the poor.[[See, for instance, Goldstein and Udry 2008.]] Increases in investment as a result of land tenure security have also shown diminishing returns as total size of land holdings increase.

Effect Period and Endogeneity

Even where LPR investments have positive long-term impacts, these effects can take time to manifest. The effect period length depends on factors such as land users’ access to credit, input and output markets. Effects on intermediate outcomes, such as perceptions and investment, will occur first with resulting productivity impacts typically lagging (e.g. a tree planted may take several years to mature). It is widely known that systematic registration programs can increase conflicts and reduce rentals over the short-run as individuals and firms attempt to establish land claims and dormant conflicts come to light.[[Gignoux, Macours, and Wren-Lewis 2014 (page 8); Goldstein et al. 2015.]] There is limited empirical analysis of the dynamics of these short-run effects, however, with the exception of preliminary evidence from Goldstein et al. (2015), who show that more precise demarcation of land boundaries in Benin was followed after 11 months by a 1.5 percentage point decline in the proportion of parcels rented out versus control parcels, relative to the baseline of 6 percent. The authors hypothesized that this resulted from landowners’ efforts to reassert their land rights by taking back property that they had been renting out, in order to stake a claim during the certification process.[[Goldstein et al, 2015 (page 24). Long term effects on parcel rentals were not yet available at the time of writing.]] Lastly, endogeneity concerns are a major obstacle to the econometric estimation of LPR investment effects. These concerns are discussed in detail in section III.Land-Attached Investment

Actors are more likely to invest in a piece of land when they are confident that they can appropriate the full social benefit of that investment. LPR investments that improve tenure security can therefore result in an investment level closer to the social optimum (i.e. the level at which the marginal cost of additional land investments is equal to the expected net present value (NPV) of returns from those investments). An extensive body of empirical literature supports this link between tenure security improvements and increases in land-attached investment. Investment types commonly analyzed include soil[[Ali et al, 2015 (page 1).]] and water conservation, livestock, machinery, crops and trees, improvements to residential housing and, in urban areas, construction of high-rise residential and commercial buildings. Three channels of particular importance are cropping decisions, infrastructure investment, and environmental conservation.Cropping Decisions

Land and transfer rights are associated with longer-term investment strategies, such as the allocation of land to perennials, trees and higher-value export crops.[[Stickler and Huntington, 2015 (page 4).]] Trees take many years to reach maturity, and therefore require a long-term investment horizon. In Ethiopia, for instance, the granting of land transfer rights resulted in a 46% increase in land allocated to perennials. In Nicaragua, owner cultivated plots were 24% more likely to be planted with trees than tenant cultivated plots.[[Dercon and Ali, 2007; Bandiera 2007.]]While tree crop and perennial investment are the most common outcomes examined in the literature, some studies have focused on the adoption of export crops. In Peru, possession of a land title was found to strongly predict a farmer’s shift from production for the domestic market to production of export crops requiring a greater up-front investment. As a result, these export-oriented farmers were less likely to be poor.[[Field, Field, and Torero, 2006.]]

In Benin, MCC funded one of the first randomized controlled trials[[A concurrent randomized trial was underway in Mongolia.]] of a land certification program to examine the link between demarcation—the first “key step” in the land rights formalization process—and investment.[[This is an example of a decentralized, participatory process for land certification that is lower cost than standard freehold land titling approaches. In Benin certificates can be converted into ownership titles so that the right is similar to a freehold title (although the rights conferred by certification are weaker in many contexts).]] As expected per the project logic, no statistically significant effect on agricultural productivity was detected at mid-line (2-years following demarcation). However, demarcation of plots had caused a 2.4 percentage point (p.p.) increase in parcels planted with perennial crops and 1.7 p.p. increase in parcels with a tree planted during the past 12 months.[[Demarcation also increased the percentage of newly fallowed female-headed household parcels by 1.5 p.p. on a base of approximately 0% (fallowing is an investment in soil fertility). This eliminated the gender gap in percentage of parcels newly fallowed (approximately 1% of male-headed household parcels were newly fallowed). Female-headed household parcels, however, made-up only 15% of parcels in the sample.]] At endline (four years later), the study found that demarcation had caused a 3.2 p.p. increase in parcels planted with perennial crops.[[No difference between treatment and control was observed for trees planted in the last 12 months at endline, suggesting that demarcation led to a long-term increase in the stock of trees but not the investment rate.]]

Private Infrastructure

LPR reform may also increase investment in land-attached infrastructure, although there is limited empirical evidence of infrastructure effects in rural areas. Bardhan, Mookherjee, and Kumar (2012) found that land tenancy registration reforms in West Bengal had a direct (Marshallian) effect on tenant demand for groundwater, which in turn incentivized groundwater sellers to invest in groundwater capacity with high fixed costs (tubewells, dugwells and submersible pumps). These investments subsequently reduced the price of groundwater, resulting in a positive spillover effect on non-tenant plot groundwater use as well. This increase in groundwater use raised productivity on both tenant and non-tenant plots.[[Bardhan, Mookherjee, and Kumar, 2012.]]In urban areas, formalization of land rights in informal settlements has been found to increase physical housing investment. In Peru, providing formal titles to informal settlement residents substantially increased investment in roofs, securing home foundations, painting walls, installing floors, and general home expansion. In Argentina, providing formal titles to informal settlement residents likewise substantially increased physical housing investments: Over the span of four years, the overall index of housing quality within the settlement rose by 37%.[[Field 2005; Galiani and Schargrodsky 2010.]]

Land rights formalization can also incentivize investment in high-rise buildings in central urban areas. Henderson, Regan, and Venables (2017) apply a general equilibrium dynamic monocentric city model to estimate the potential welfare effects of formalizing land rights in informal settlements in Nairobi to enable investment in high-rise buildings near the city center. After calibrating the model using a combination of remote sensing data from 2003/2004, household survey data from 2012, and land price data scraped from a property sale website for 2015, they find that the immediate conversion of all informal land in Nairobi would yield an aggregate gain of $759 million in present value versus the counterfactual of informality in perpetuity. This is equivalent to a welfare gain of $13,000 per household living in Nairobi’s informal settlement areas, where median housing expenditure is $260 per annum. The welfare gain versus the counterfactual of conversion of all informal areas in 30 years is PV $125 million, or $2,141 per informal settlement household.

Regulatory reform to remove building height restrictions can similarly incentivize investment in high-rise buildings in central urban areas. Bertaud and Bruecker (2005) estimate the welfare cost imposed by Bangalore’s building height restriction at between 3 and 6 percent of household consumption. Similarly, Lees (2014) applies a simple, calibrated monocentric city model to estimate potential gains from removing building height restrictions, density restrictions and other regulations in Auckland, and finds an average household gain of $933 per annum. These estimates do not account for the loss of some public amenities, such as improved views, that would result from removing height restrictions.

Glaeser, Gyourko and Saks (2005) analyze the effect of building height restrictions in Manhattan while attempting to account for the negative externality of increased heights on building views. The analysis shows that the price of a Manhattan high rise floor is typically more than twice its supply cost, and presents evidence that height restrictions are the primary cause of this gap. They apply a hedonic price regression to estimate the negative externality on views that would result from removing height restrictions, and find that this would justify a construction related regulatory tax equal to only 12.5% of apartment values. The value of views or other amenities resulting from land use regulations will, of course, vary by context. In estimating the effect of removing city level building height restrictions on land rents, it is also important to account for general equilibrium effects, since land rents will increase in the central business district, but reduce at the city outskirts.[[Models will typically set a floor for land rents on the outskirts at the agricultural value of land.]]

These monocentric city models typically incorporate effects of increased building heights on economies of scale in building construction,[[Above some base height (around 7 stories) and below extreme heights (perhaps 50 stories), increases in building height reduce the mean cost per square meter of built space by leveraging fixed costs of construction (Glaeser, 2011).]] and reduction in transport costs resulting from households relocating closer to the central business district. Many analyses exclude negative crowding externalities, however, that can result from increasing building heights including blocked views, increased pollution in inhabited areas and possibly reduced public service quality (in contexts where public service capacity in the central business district is insufficient). Many analyses also exclude potential positive externalities in the form of reduced road congestion for households remaining in the city outskirts, economies of agglomeration in production and consumption, and possibly reduced public service delivery cost (in contexts where users are not charged the full cost of these services).

Environmental Damage

Improved land governance can reduce costly environmental degradation resulting from coordination failures, poor land planning, unsustainable natural resource management, and weak protection of public interests. Land tenure security is associated with greater investment in soil conservation, erosion mitigation, and tree planting. Improvements in tenure security may also reduce deforestation, although other factors are stronger determinants and the relationship may vary by context.[[Robinson, Holland, and Naughton-Treves, 2014; Ferretti-Gallon and Busch, 2014.]] Weak protection of land owned or managed by the state can likewise lead to deforestation through conversion of forests to farmland, or other private uses.In Uganda, farmers with weak tenure security were incentivized to maximize short-term output, resulting in greater inorganic fertilizer application. Farmers with stronger security, however, were incentivized to preserve long run output, resulting in a shift toward organic fertilizer application. Tenure security provides farmers with “longer planning horizons,” which can incentivize them to adopt sustainable and environmentally beneficial practices such as soil conservation, organic fertilizers and land fallowing. Likewise, a 2007 study found that farmers and land owners who were assured they would be able to remain on land and pass it to their inheritors had a strong interest in preserving the land for future use.[[Birungi and Hassan, 2010; Kabubo-Mariara, 2007.]]

Tenure security can also lead to a decrease in deforestation. Residents of forested areas in Thailand that lack tenure security, for example, have been shown to cut down trees and plant perennial crops in their place as a means of documenting their long presence on the land and, eventually, petitioning for formal titles to the land.[[Wannasai and Shrestha, 2008.]] While this study focused on a particular region in Thailand, the authors noted similar findings in research from other low-income countries. In Sumberjaya, Indonesia, conditional and temporary land tenure was used to incentivize farmers to commit to ceasing deforestation practices on 10% of Indonesia’s remaining forested land. Impact evaluations showed that deforestation rates decreased and farmers’ incomes increased by almost 30% by removing the necessity to pay bribes to avoid eviction.[[Wendland et al, 2010.]]

In Brazil, fear of government-led, rental-targeted expropriation policies discourages landowners from renting unused land to more productive users. This disconnect between supply and demand causes farmers to expand outward from vacant land to the Amazon rainforest. According to Alston and Mueller, corrective land tenure reform policies could slow this destructive degradation of the Amazon, and also increase productivity.[[Alston and Mueller, 2010; Lawry et al, 2014 (page 19).]]

For land policy reforms to have a lasting effect, however, property rights must be recognized in the cultural, ecological, social, and legal context. For example, many indigenous communities engage in communal property rights, as opposed to individual rights. This can be an advantage in the case of land tenure reform’s environmental effects, as is shown in Ecuador, where these communities have been noted to have a more long-term and sustainable “vision” of land use than individuals. It has been increasingly seen as beneficial to transfer the authority of moving resources such as wildlife or water, which are usually owned by the state, to more local authority, such as “user groups.” In Ecuador and Indonesia, communal tenure systems provided favorable special arrangements, as opposed to the common fragmenting caused by private demarcation, as well as more resilient contracts through social sanctions.[[Wendland et al, 2010; USAID, 2007 (page 8-9).]]

Conversely, a later study of property rights in Ecuador found that there is very little evidence demonstrating a direct link between titling and forest cover, and that research that attempts to draw conclusions on the relationship between tenure formalization and deforestation based on simple regressions is dangerous and “on weak empirical footing.” More research is needed to rigorously examine links between property rights and deforestation.[[Buntaine, Hamilton, and Millones, 2014 (page 24).]]

Land Transfer

LPR interventions can also improve productivity by incentivizing the transfer of land parcels to parties who have a comparative advantage in their use. This increases productivity both by transferring land to households and firms who are able to use land relatively more productively and by allowing households and firms leasing-out or selling land to engage in other, non-land intensive activities in which they are relatively more productive. For instance, Jin and Deininger 2009 show that land rental in China increased productivity per hectare by 60%, with one third of these gains allocated to landlords and two thirds to tenants. This resulted in a net increase in tenant income of 25%, and an even greater increase in the income of households leasing-out land through transition into non-farm employment. Similar gains from efficiency and productivity were observed in Albania, Vietnam and Hungary.[[Deininger, Carletto, and Savastano, 2007; Nguyen, 2008; Vranken and Swinnen, 2006.]]Land tenure security in the presence of land administration services with the capacity to efficiently register transactions encourages growth of the land rental market, which is associated with greater access to land by the poor.[[Lawry et al, 2014 (page 49).]] Both land tenure security and functional rental markets are also associated with economic growth through more efficient use of land. Conversely, when landlords feel insecure about their land rights, they may choose not to rent out land for fear it would be expropriated.[[Alston and Mueller, 2010.]] Strengthening land and property rights can lead to a greater sense of security among households, which in turn leads to greater participation in the land rental and sale markets by both renters and landlords. This spurs the reallocation of land from less efficient to more efficient users through the rental market, and increases the likelihood that users will have the opportunity to profit from economies of scale.[[Holden, Deininger, and Ghebru, 2009; Chand and Yala, 2009.]]

Much of the literature focuses on the positive effects of land rights on the size of the land rental and sale markets. This growth in the land rental market was observed across geographical regions and cultures: specifically in Albania, the Dominican Republic, Ethiopia, and Vietnam.[[Deininger, Carletto, and Savastano, 2007; Macours, de Janvry, and Sadoulet, 2010; Holden, Deininger, and Ghebru, 2011; Nguyen, 2008.]] In each of these countries, researchers were able to connect the institution of formal land rights with greater participation in the rental and sale markets. The geographic diversity of these findings suggests that “the provision of clear, enforceable, and secure long-term [land] rights is an essential pre-condition for the operation of land rental market”[[Nguyen, 2008.]] and could hold true in various regions and communities.

The reduction of user fees for registering land transfers and other land administration activities has also been shown to increase land market activity through a price effect. When additional costs are added to a transaction, buyers and renters compensate by lowering the price they are willing to pay, while sellers and lessors raise the price that they are willing to accept. This reduces the overall volume of land transactions and may increase the portion of transactions that are informal.

Researchers have found several positive outcomes of increasing land market activity. One such outcome points to improving land access for poorer households. The rental market provides an opportunity for those effectively shut out of the land purchase market to gain access to land. In the Dominican Republic, for example, researchers found that through improvements in the “security of property rights, the area and the number of plots rented to poor tenants would increase by 63–65%,” and a similar redistribution was found in Vietnam. In Albania, however, a growing rental market occurred but did not necessarily benefit the poor. In this instance, land access improved for those members of the community that were simply the most interested in agriculture, regardless of their level of income.[[Macours, de Janvry, and Sadoulet, 2010; Nguyen, 2008; Deininger et al, 2007.]]

Another major outcome of stronger land rental and sale markets resulting from land tenure security is the transfer of land to more productive users. In the absence of sufficient land security, land holders tend to rely on social sanctions to enforce land transfer agreements, thus making transactions with persons outside of the community inherently more risky. This uncertainty can lead to sub-optimal market participation and inefficient market segmentation from efficient users to users who are less efficient, but are in the familial network of renters.[[Jin and Deininger, 2009.]] This efficiency differential is indicated in rental prices that are 80% higher to non-relatives than to relatives (although this could also be explained by families’ desire to sacrifice profit in order to help other members of the family or community).

In many contexts, households with low tenure security who would otherwise engage in non-farm work continue to cultivate parcels out of fear that the parcels will otherwise be expropriated. A related phenomenon in urban informal settlements is maintenance of a physical presence on parcels to establish ownership by household members who would otherwise enter the labor market. As land was legally secured in informal settlements in Peru, for example, subjects were shown to have been more likely to join the labor force, possibly as a result of no longer needing to maintain physical presence on the land to ensure claim over it. Men, who tend to have greater earning potential outside of the home, are the most likely to stay at home to defend the property when land rights are not secure.[[Field, 2005; Field, 2007; Lanjouw and Levy, 2004 (page 918 and 920); Hallward-Driemeier and Gajigo, 2011.]]

Lastly, there are some caveats presented in the literature. In Albania, land rights had a limited effect on rental market participation. The most important determinant of participation was years of formal education, which was found to be inversely proportional to agricultural labor market participation. Those with higher levels of education were more likely to rent out their land and less likely to rent in additional land. The effect of education on the Albanian rental market was much greater than the effect of land rights. In Hungary and China, where land titles have already been distributed, high transaction costs limit the transfer of land through sale or lease.[[Deininger, Carletto, and Savastano, 2007; Jin and Deininger 2009; Macours, de Janvry, and Sadoulet, 2010.]]

Evidence from Hungary also shows that search and administrative transaction costs can remain an obstacle in the land rental market even after a land tenure reform and titling process has been completed. Similarly, in nearby Albania, transaction costs remained high following the implementation of a land tenure reform and titling process. Landowners in that country used intra-family transfers and inheritances to circumvent the high transaction costs. This suggests that following land tenure reform, transaction costs can remain a major obstacle to an efficient land rental/sale market.

While establishing strong but less-transferable (inalienable) rights inhibits land sales, it can sometimes facilitate land rentals. This is because having strong rights that cannot be transferred to others makes it easier for the landlord to reclaim the property at the end of the lease period,[[Lanjouw and Levy, 2004 (page 901).]] but nearly impossible to sell the land outright. A similarly weak sale market for land can be observed in communities reliant on customary rights due to the inalienability often associated with this type of land rights. USAID’s 2015 exploratory analysis found that in Liberia, Zambia, and Guinea, where customary land rights are mostly inalienable, 80% of interviewed Liberians reported that they do not have the right to sell their land, 6-7% of Zambians reported renting or borrowing land from other households, and only 3% of Guineans reported rental income in 2014.[[Stickler and Huntington, 2015 (page 19).]]

Access to and Cost of Finance

It is theoretically possible that LPR reform can allow households and firms to pledge property as collateral against loans and thereby increase access to credit that finances investments whose returns exceed the cost to banks of providing those loans, as argued by De Soto (2000). The willingness of creditors to accept and borrowers to offer land as collateral for a loans, though, also depends on the sophistication of the legal system (ability to protect both borrower and creditor) and financial sector, as well as the income level of potential borrowers and the size and location of the parcels to be used as collateral (creditworthiness of the potential borrower, and value of the parcel to the creditor in foreclosure).In practice, the balance of empirical literature has found little to no effect of LPR reform on credit access. While some regions (such as Cambodia, Guatemala, Ethiopia, and Argentina) have demonstrated a rise in the provision of credit following the institution of land rights policy, the effects were very modest. In these cases, a land title supplied the borrower with a form of collateral. This additional collateral allowed persons to obtain a loan that would not have been available to them otherwise, or enjoy a small reduction in interest rate relative to a similar loan that lacked the backing of collateral.[[Markussen, 2008; Macours 2009; Hallward-Driemeier and Gajigo, 2011; Galiani and Schargrodsky 2010. Note that it is not the case that LPR project effects on investment depend on increased credit access. For example, data from Argentina, Mexico and Nicaragua all show increased investment, but little to no impact on access to credit from the issuance of formal land rights, with the exception of a “modest but positive effect” on mortgage credit in Argentina. Likewise, increased credit access resulting from LPR projects does not necessarily result in increased investment. In Zambia, title- and lease-holders achieved greater credit access, but this did not clearly translate into greater investment, implying the loans were used for consumption smoothing.]]

When investigating the effect of land rights on credit, it is necessary to consider the sophistication of the region’s financial and legal systems and the types of institutions providing the credit. For example, the possession of a land title has a greater influence over credit decisions in regions with a longer tradition of market-based economic policies. The free-market traditions in southern Vietnam relative to the centrally-planned economy of northern Vietnam is a good example of this discrepancy. In southern Vietnam, certification increased the likelihood of obtaining formal credit by as much as 14%. In northern Vietnam, on the other hand, the effect of certification was not significantly different from zero in most estimates. Likewise, a formal financial institution is more likely than an informal one to consider a land title when making a credit decision. Large, national banks that explicitly consider collateral are more likely to provide credit to titled applicants than are smaller institutions or informal channels, such as moneylenders or family and friends. One example of this was found in Argentina, which exhibited a modest uptick in mortgage credit as a result of land title, but no effect for other forms of credit. A 2015 systematic review of proposed reasons for this include unattractive characteristics of the properties and the weak “bankability” of the borrowers. Therefore, these effects are somewhat more likely in urban areas and in contexts with larger, more bankable potential lenders.[[Kemper, Klump, and Schumacher, 2011; Galiani and Schargrodsky 2010; Lawry et al, 2014 (page 63).]]

Offering credit to low-income borrowers collateralized with small plots of land is often unprofitable for banks. Moreover, poor households with few assets beyond the land are often unwilling to risk losing the land by putting it up for collateral and so rely instead on credit through traders, ROSCAs, or group lending.[[Lanjouw and Levy, 2004 (page 934).]] Because of this, the benefits from increased credit access may disproportionately accrue to higher income households.

The possession of a land title is often not the constraint to bank lending to low-income consumers, but rather the inadequate enforcement of land rights laws and policies. In the case of Peru, land titles have little value to banks and other lending institutions, because the government has failed to endorse the formal land rights it has issued. Similarly, there is no legal mechanism in Vietnam for banks to seize property in the case of default.[[Kerekes and Williamson, 2010; Do and Iyer, 2008.]] In both instances, a land title alone cannot serve as an adequate form of collateral to support a loan. Without the legal underpinning to support timely foreclosure, the land title itself has little to no effect on the supply of credit in an economy.

Cost of Land Administration Service Delivery

LPR interventions can also directly reduce the administrative and user costs of executing land transactions, first time registration and mapping of parcels, and resolving land conflicts. Costs include the actual administrative cost of delivering services, which may differ from the user fee charged for the service, as well as any user costs not paid to the land administration institution (such as vehicle operating and opportunity costs of travel to land administration offices). The magnitude of direct benefits from cost reduction will depend on 1) the size of the potential cost reduction, and 2) the total volume of administrative processes targeted. One indication of the potential for efficiency improvement investments to reduce costs is the substantial variation in parcel registration costs. The cost of registering a parcel transfer for 173 countries included in the World Bank’s 2008 Doing Business Survey was 2 percent or less of the parcel value for 19% of cases, but 5 percent or 10 percent for 53% and 24% of countries, respectively.[[WB Doing Business 2008; Calculations from Deininger and Feder, 2009. Note that the Doing Business indicator refers to the cost to register the transfer of an existing commercial parcel, rather than transfer of a residential parcel or greenfield investment involving land allocation.]] In Lesotho, the total days required to register property declined from 101 to 43 following introduction of a new Land Law in 2009 and related establishment and capacity building of the Land Administration Authority to implement the new Land Law and streamline procedures as part of MCC’s Lesotho I Compact. In Jamaica, institutional and administration reforms reduced property registration and transfer times from 70 to 30 and 25 to 5 days, respectively, while reducing survey check times from 182 to 35 days. During the same period, the proportion of agency costs covered by revenues increased from 50% to 75% while total expenditures rose from 320 to 615 million JMD in nominal terms.[[WB Doing Business 2010 and 2013; Gainer, 2017.]]Although less common, LPR interventions may also target reduction in the cost of existing systematic registration and mapping activities. While early land titling projects were often cost inefficient, advances in project design, information technology and remote sensing have potential to drastically reduce the cost of some LPR interventions.[[Jacoby and Minten, 2007; Deininger, Ali, and Alemu 2011; Holden, Deininger, and Ghebru, 2009.]] One source of past inefficiency has been overstatement of the effect of mapping precision on tenure security, which led to overspending on surveying precision. Since surveying cost increases exponentially with increased precision, this resulted in bilateral or multilateral funded first-time registration projects that cost on average $20-$60 per parcel, and sometimes above $100 per parcel. In contrast, use of low-cost certification methods with high community participation in Ethiopia allowed registration of 20 million plots at under $1 per parcel.[[Burns et al, 2007; Deininger, Ali, and Yamano, 2008. Although, this certification process involved little mapping, which may limit strength of the awarded rights. LPR investments may also improve the efficiency of and reduce dead weight loss from revenue mobilization, although these effects are not covered by this document.]]

Land Use Regulation

LPR investments may introduce regulations to redefine the allowed uses of land in ways that reduce the cost of non-land public service delivery (e.g. water and wastewater, electricity, and road infrastructure and public transport) or negative externalities from colocation of incompatible uses (e.g. excessive noise or poor air quality proximate to residential areas).[[These benefits may manifest both as a direct increase in land value and as an incentive to make investments that increase land value beyond the investment cost. Where land users are not charged the full cost of public service delivery, however, land value changes may either over or understate benefits.]] For example, Paul Romer has highlighted the importance of establishing and publicly securing arterial roadway grids in undeveloped areas before private investment occurs. Early definition of the arterial grid and securing it to the state averts the high cost of either converting private land to public use in the future or allowing the persistence of informal settlements without access to public services.[[See, for instance, Fuller and Romer 2014. Urban informal settlements are, “contiguous settlements where inhabitants are characterized as having insecure residential status, inadequate access to safe water, inadequate access to sanitation and other basic infrastructure and services, poor structural quality of housing, and overcrowding” (UN-Habitat, 2003).]] In Peru, residents of informal settlements paid high prices to access water from private providers until formalization of land allowed access to services at a lower price and higher quality.[[Cantuarias and Delgado 2004; and Durand-Lasserve and Selod 2009]] LPR policies may also aim to incentivize land-attached investments in areas where public service delivery capacity is greater or will be less expensive to expand in contexts where users are not charged the full cost of delivery of these services.[[Nunns and Rohani, 2014.]]Perception of Tenure Security Improvement Mediated by Conflict Reduction, Inheritance Rights and Other Intermediate Outcomes

Several studies examine the effects of LPR interventions on intermediate outcomes that affect household incomes through the above mechanisms. For example, much of the literature finds that land titles are associated with a lower incidence of land conflict, a decrease shown to be as high as 20%. This reduction in land conflict is, in turn, associated with increased investment and transfer of parcels, resulting in higher productivity. In Burkina Faso, tenure insecurity resulting from perceived risk of land conflict or expropriation was found to reduce overall agricultural productivity by 9%. The effect of land titling on conflict is greater in regions where the number, duration required to resolve and severity of conflicts is high. Even in contexts where few conflicts occur, serious conflicts may increase the perceived risk of conflict for a large number of households, discouraging investment and land transfer, especially when these conflicts are with parties external to the community (government authorities, herders, etc).[[Macours, 2009; Deininger and Castagnini, 2006; Deininger and Jin, 2006. In addition to affecting perceived tenure security, land conflict reduction may also have a more direct economic effect through the channel of reduction in the administrative and user cost of resolving land conflicts.]]Likewise, many studies investigate LPR effects on perceptions of inheritance rights, an important determinant of perceived tenure security. Two recent studies in Rwanda found that land tenure reform pilots there increased certainty regarding who would inherit land. Both studies saw a reduction in “succession-related uncertainty” and, interestingly, girls were nearly as likely as boys to be the named inheritor of land in most situations. This near gender equality, however, broke down among very poor and female-led households: two instances in which boys were more likely to inherit. The authors noted, however, that the preference for male heirs in these cases seemed to arise from cultural norms rather than from the land tenure regime itself. To the point of inheritance, data suggest that the family members most likely to pursue a career in agriculture tend to inherit the land, serving as an example of greater production efficiency through inheritance.[[Santos, Fletschner, and Daconto, 2014; Ali, Deininger, and Goldstein, 2014; Deininger, 2007. “Succession-related uncertainty” is the probability of a household reporting that it is unknown who will inherit a parcel.]]

Conclusion

Well-designed LPR investments can achieve benefits through a variety of channels, including land-attached investment levels closer to the social optimum, allocation of plots to more efficient users, reduction in the user and administrative costs of delivering land administration and other public services and, in some contexts, increased access to credit. LPR impacts, however, are highly sensitive to local context, including baseline levels of tenure security and functionality of existing systems, the presence of complementary inputs on which economic impacts are contingent, and the supporting political and institutional environment. Effects are also highly sensitive to the quality of the project design and the degree to which it is tailored to the local context. Where the local context is inappropriate for a LPR intervention or projects are designed without awareness of existing systems and conditions, LPR investments can have neutral or even negative economic and distributional impacts. Even for cases where the impact of LPR investments are positive, the trajectory of this impact may be non-linear. Lastly, the estimation of potential LPR project effects is fraught with endogeneity concerns, discussed in detail in section III.LPR Investment Typology, Economic Logic and Analytic Requirements

LPR investments include a wide range of context-specific activities for which an exhaustive taxonomy is difficult to assign. Many LPR investments also include multiple activity types. For example, MCC investments have often combined activities that clarify and publicly record land rights with reforms to land governance policies and institutions, and improvements to land administration systems. Despite the wide range and frequent combination of activities in practice, Table 1 attempts to broadly group LPR activities in a way that is useful for considering estimation of their economic rates of return (ERR). Based on the table, this section defines 6 investment types, along with their benefit streams and the data required to estimate their magnitude.[[This typology includes common MCC LPR investments; the typology may expand in the future as MCC country teams identify new investment types to effectively address the root causes of binding constraints in particular country contexts.]] Section III presents principles to guide the selection of existing data (and where necessary collection of original data), as well as the selection and application of methods to estimate the magnitude and distribution of LPR investment benefits and costs.Clarification of Property Rights and Boundaries

Many LPR investments focus on clarifying property rights and boundaries. These activities often resolve land conflicts, more formally recognize land use rights, map parcel boundaries, and/or securely record and publically display land use rights and parcel boundaries in a formal registry, cadaster or other public record. These investments commonly involve the delivery of policy inputs that expand the coverage of existing land administration institutions and their services to new areas. As discussed above, the economic logic for these activities is that clarifying property rights and boundaries will improve perceived tenure security, leading to increased investment, land transfer and (in more limited cases) credit access.To inform CBA of these investments, the analyst should ideally obtain data on perceptions of tenure security, land value (if land market functional), incidence of land conflict, land investment (including housing), land transfers (sale/rental) and demand for and use of land administration services both in potential investment areas and, if possible, in similar areas where the proposed land administration services are already provided and/or property rights and boundaries are relatively clear. For rural areas, the analyst should also obtain household data on agricultural production, non-farm enterprises and wage employment; while for urban areas the analyst should obtain data on household-based business activities and any mortgage registrations. In some contexts, data on credit access and use may be necessary as well. In addition, the analyst should obtain administrative data from the implementing partner(s) including the number and cost of registrations, mappings, transfers, conflicts resolved, and mortgages/mortgage bonds, as well as administrative land transaction times.[[The economist should closely collaborate with the M&E lead, land sector lead, and gender and social inclusion (GSI) leads both in selecting existing data and in any collection of original data. These team members must review any instrument used for original data collection to inform economic analysis. See section III for guidance on questionnaire design and data collection.]]

Building Capacity of Land Administration Institutions

Other LPR investments aim to improve the efficiency of national, regional and local land-administration authorities (which may include traditional authorities and land boards) through streamlining and strengthening institutions, operations, procedures and information technology. This may include, for instance, the development and installation of land information and transaction systems (such as computerized registry and cadaster databases, as well as systems to link these databases with courts, banks, the tax authority and other agents); installation of geospatial mapping infrastructure; financial/HR capacity strengthening; staff training; improvement to the capacity of courts or other conflict resolution institutions to process and resolve land conflicts predictably and speedily; improved development and management of industrial zones; decentralization or even the establishment of a new agency. The economic logic of these activities is that they will reduce the cost of land administration service delivery (including administrative costs of land conflict resolution), and/or improve its quality such that perceived tenure security increases leading to increased investment, land transfers and credit access. These activities may also be a necessary precondition for or improve the quality of land use planning activities (considered separately below).Cost savings can be calculated as the reduction in the average cost of registering, mapping or transferring a parcel, resolving a land conflict, or verifying a parcel’s boundary and owner to facilitate transactions and enforcements (by courts, banks, the tax authority, etc) times the incidence of these activities. The average cost estimate should include data on any time and travel cost incurred by service users. For instance, if the activity allows users to access land administration services at the district rather than national level, the resulting reduction in user time and travel expense should be reflected in the cost reduction.

Administrative data obtained for the ERR calculation should include the total number of registrations, mappings, transfers, conflicts resolved, and verifications of parcel boundaries and ownership (to facilitate transactions and enforcements) occurring per year, and the total fixed and variable costs of administering them. Administrative data on the mean number of user visits and total time required to complete a given administrative process should be collected as well.[[The economist should closely collaborate with the M&E lead, land sector lead, and gender and social inclusion (GSI) leads both in selecting existing data and in any collection of original data. These team members must review any instrument used for original data collection to inform economic analysis. See section III for guidance on questionnaire design and data collection.]] If available, any survey data on users’ cost of travel to nearest service center and opportunity cost of time (ideally the user’s wage) should be obtained, as well as data on the return on investments delayed by the total administrative process time relative to the return on the next best use of that investment capital during the processing period. Information on the extent of informal transactions and the reason for informality (high formal transaction costs, lack of information, etc) within areas covered by a formal land governance system may also provide useful information on risks to the sustainability and effectiveness of that system. If the activity is believed to increase the quality or uptake of land administration service delivery, the data listed above under clarification of property rights and boundaries should be collected as well.

Increasing Awareness of Land Rights, Regulations and Administration Services

Another common investment type targets increased awareness of land rights, regulations and land administration services. This includes public awareness and education campaigns to inform individuals of their land rights and to encourage use of registration, mapping, transfer and conflict resolution services. The economic logic for these activities is that they increase perceived tenure security both directly by changing knowledge and beliefs, and indirectly by increasing use of formal registration, mapping, transfer, and conflict resolution services. This increase in tenure security, in turn, increases investment, land transfer and credit access.The main benefit streams and ERR data requirements are the same as those listed under clarification of property rights and boundaries above. Data on the extent of informal transactions and the reasons for informality (high transaction costs, lack of information, etc) within areas covered by a formal land governance system may also provide useful information on risks to the sustainability and effectiveness of that system. In addition to those data, M&E data should ideally be collected on individuals’ exposure to the campaign, change in knowledge, change in belief, and resulting change in behavior to inform the Closeout and Evaluation-Based CBA Models.

Land Use Planning and Natural Resource Management

LPR investments may also aim to improve land use planning and natural resource management. This includes activities such as urban planning, land use classification, land resource mapping, and community-based natural resource management. As discussed above, the economic rationale for these investments is that they redefine the allowed uses of land in ways that reduce the cost of non-land public service delivery (e.g. water and wastewater, electricity, and road infrastructure and public transport), negative externalities from colocation of incompatible uses (e.g. excessive noise or poor air quality proximate to residential areas), or negative externalities from inappropriate uses (e.g. pollution, degradation of common land through overgrazing).For land use planning investments expected to substantially reduce the cost and improve the quality of future non-land public service delivery, the analyst should ideally obtain data on the cost of service delivery in similar areas with and without the land use planning improvements under consideration. The analyst should consult the respective sector guidelines (e.g. WASH, Power, etc) to determine data requirements to estimate potential benefits from improved access to and quality of each service the LPR investment is expected to affect. For activities aiming to reduce incompatible or inappropriate use of parcels, data on land values and/or agricultural productivity and their respective determinants (including the cost of any land-attached investments), and information on proximity to the incompatible/inappropriate use the activity seeks to relocate/reduce should be obtained. Similar data should be collected for activities expected to improve management of common parcels, both for potential project areas and for similar parcels that are better managed.

Legal, Regulatory and Policy Dialogue and Reform

While the above four investment types affect beneficiaries more directly, many LPR investments affect beneficiaries indirectly by supporting partner government efforts to design, authorize and implement legal, regulatory, and procedural and policy reforms. This would include activities to develop the legal, regulatory, procedural and policy foundations for land administration and land management, establish a new land administration authority or court/judicial institution, adapt regulations to better implement existing land laws, reform procedures to streamline and simplify, and build capacity and awareness of public officials responsible for designing, authorizing and implementing reforms.Since these reforms ultimately impact beneficiaries through one or more of the four direct activity types above, they have the same benefit stream categories as the direct activity they aim to affect, but with the additional cost streams (and risks) of the preceding reform design, authorization, and implementation steps. Likewise, the data requirements for their ERR estimation include those listed for the four activities above, but relevant household, firm, and/or administrative data must be obtained for a sample that is informative for the entire area in which the reforms are expected to affect economic outcomes. Intervention and context specific data must also be obtained for the expected inputs and outputs of the reform investment. The analyst should work with the country team to identify each step in the reform process at which there is a risk of partial or complete failure of or delay to the reform process and obtain as much information as possible to inform assignment of some probability to these outcomes for purpose of estimating the expected value of project benefits and costs (see MCC’s PIR CBA Guidance).[[Note that investments of this type correspond to investments at level 4a (Sector Policies) and 4b (Institutions of Sector Governance) in MCC’s PIR CBA Guidelines.]] For cases where land sector reform is likely to have substantial general equilibrium effects, additional data may be necessary to calibrate an appropriate model.[[See Henderson, Regan and Venables (2017) for an example of data requirements for a monocentric city model.]]

Facilitation of Land Access and Land Allocation as Part of a Broader Contingent Investment

Lastly, investments that facilitate land access and allocation are often classified as LPR. These include, for example, investments that design and implement processes for land allocation as part of contingent irrigation, industrial zone, or other infrastructure development or improvement. Their primary benefit stream is that of the contingent investment and, in general, their costs should be included in the ERR of the contingent project. In some cases (for example, in the case of irrigation investments) the beneficiary stream of the contingent investment will be similar to that of a typical land investment (increases in land productivity or price), so that any benefits specific to the land investment would be infeasible to disentangle.Investment Logic Models

Based on the above discussion, Figure 1 provides a compact high-level economic logic for LPR investments. For a useful comprehensive LPR investment logic, see Lisher (2018).[[Note that this comprehensive logic, however, includes several benefit streams for which existing evidence is insufficient for inclusion in ex-ante CBA models.]] Figure 2 provides an example of a detailed program logic for a specific LPR investment, taken from MCC’s Burkina Faso Rural Land Governance Project. MCC Economists must work with the Country Team to develop a detailed program logic for every investment. This example illustrates how many of the above activity types may be combined into a single investment program. The following section presents principles to guide the selection of existing data (and where necessary collection of original data), as well as the selection and application of methods to estimate the magnitude and distribution of LPR investment benefits and costs.| ACTIVITY TYPE | BENEFITS | ESSENTIAL DATA | EXAMPLES |

| 1. Clarification of Property Rights and Boundaries | Improved perception of tenure security leading to increased investment, land transfer and (in more limited cases) credit access |

|

|

| 2. Building Capacity of Land Administration Institutions | Reduced cost of land administration service delivery, and/or improved service quality or uptake leading to improved tenure security and increased investment, land transfer and credit access |

|

|

| 3. Increasing Awareness of Land Rights, Regulations and Administration Services | Increased registration, mapping, and transfer of parcels and use of conflict resolution services, leading to improved tenure security and increased investment, land transfer and credit access |

|

|

| 4. Land Use Planning and Natural Resource Management | Reduced cost of non-land public service delivery; reduced negative externalities from colocation of incompatible uses and/or negative externalities from inappropriate uses |

|

|

| 5. Legal, Regulatory and Policy Dialogue and Reform | Benefits for direct activity types 1-4 above, with the added uncertainty of a causal link between expense on reform design, authorization and implementation and direct activity improvements. |

|

|

| 6. Facilitation of Land Access andAllocation as Part of a Broader Contingent Investment | Benefit streams of the contingent investment |

|

|

| * The above include beneficiary specific interventions (e.g. interventions targeting a specific gender, or socially and ethnically marginalized populations) | |||

| Higher Real Incomes | |

| ↑ | |

Increased Land Productivity/Value

|

Cost Savings

|

| ↑ | |

|

|

| ↑ | |

|

|

| Longer-term/Post-Compact Outcomes (3-5 years-Phase 1: 2016/ Phase 2: 2017) | Increase Productivity from Existing Uses: Increased investment, incl. farm inputs, ag inputs (machinery & buildings) & land inputs (irrigation, terracing, drainage, fallowing and soil conservation) leading to higher output & productivity | ||

| Increase in Productive Investments by Households& Firms: Shift in land use patterns (higher value crops, shift to non-ag activities & cultivation expansion) | |||

| Improved Knowledge to Productively Allocate & Invest in Land: Improved access to land, land allocation and utilization | |||

| Shorter-term/End of Compact Outcomes (1-2 years Phase 1: 2013; Phase 2: 2014) | Increase Ability to Realize Full Returns from Investment: A. Increase tenure security B. Avoid loss/damage of property C. Increase formal transactions | Direct Savings

|

|

| Outputs |

|

Establishment of local level institutions to provide land administration and conflict resolution services in project communes, staff training, and operationalization | National Assembly adoption of laws and decrees to improve rural land law (chartes foncieres, SFRs, land registry, land info system, cadaster creation, immovable property rights, land title, land management rules and topographic standards) |

| Improved national, regional & provincial land administration: land registration and mapping capacity (CORS) | Local Legislation: Implementation of national laws and decrees in Project communes, including establishing operating standards for SFRs, CFV, CCFVs, adopting chartes foncieres and ensuring similar processes and documents for APFRs | ||

| Activities | Clarification and Formalization of Property: Land Registration and Titling | Strengthening of Land Administration Agency: Institutional Reform and Capacity Building | Legal, Regulatory and Policy Reform to Strengthen Property Rights and Enable Land Markets: Rural Land Law Development |

| Source: MCC country team staff | |||

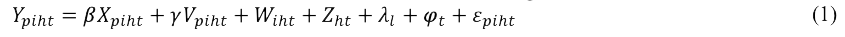

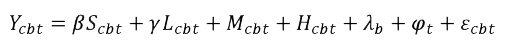

Economic Analysis of Land Sector Investments

Land CBA Process and Timing