In Principle

The Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), along with many other donors, has committed to spurring economic growth in developing countries as a means of reducing poverty and improving livelihoods. Given that the primary asset of the poor is their labor, a growing economy without job growth is by definition not inclusive of the poor. Yet, as the United Nations notes, “in 2018, one fifth of the world’s youth were not in education, employment or training… [and] young women were more than twice as likely as young men to be unemployed or outside the labor force and not in education or training.”[[United Nations Economic and Social Council. 2019. “Report of the Secretary General.”]] In the face of such challenges, it is no surprise that the transition of youth from education systems into the workforce has become a policy priority across the developing world.Historically, Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) systems have been used by governments to provide skills needed for employment. In developing countries however TVET programs have struggled to deliver due to poor quality and weak links to the labor market. When private sector demand is lacking, boosting the availability of TVET skills is unlikely to result in better employment prospects for graduates. However, when TVET programs are implemented in response to tangible skills gaps and with productive links to employers, examples of strong programs do exist.

In Practice

Since 2007, MCC has commited over $340 million in support of Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) programming across 11 programs in seven partner countries with the goal of helping their people develop the skills demanded by the labor market to increase employment and, ultimately, spur economic growth.MCC’s “First Generation” of TVET programs (implemented between 2008 and 2014) included $148 million of investments in El Salvador, Mongolia, Morocco, and Namibia. The programs included new/rehabilitated training facilities and equipment, student scholarships, training of trainers, and national policy reform. A “Second Generation” of TVET projects began with MCC’s Georgia II Compact in 2014.

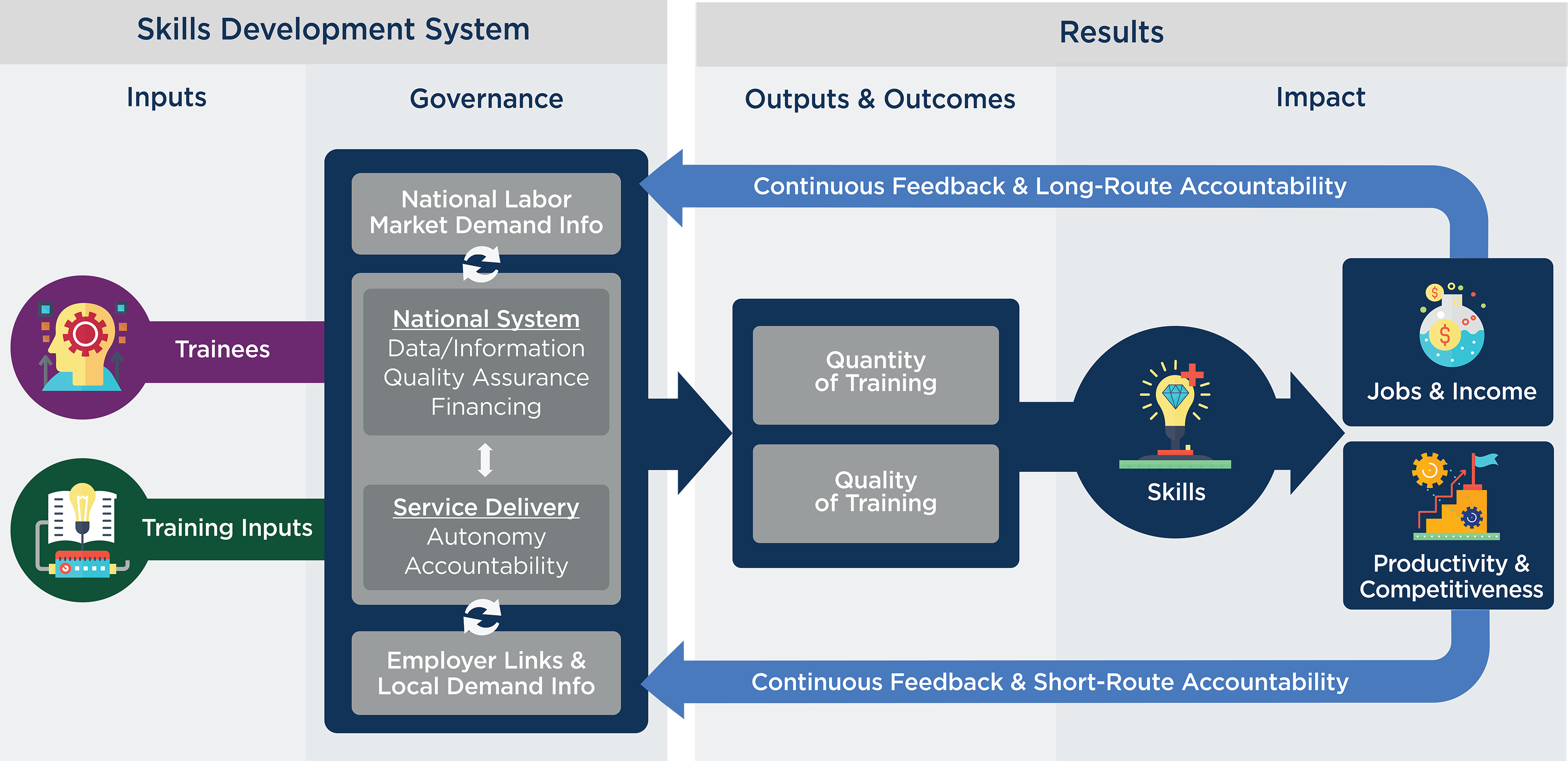

The First Generation of TVET investments produced their planned outputs in terms of new or renovated infrastructure, curricula developed, and number of participants trained. However, those projects delivered neither the desired impacts of jobs and income for trainees nor improved productivity for firms. Principles into Practice: Training Service Delivery for Jobs and Productivity presents MCC’s learning from those experiences as well as from developing a Second Generation of TVET programs. That learning identified accountability relationships, especially between employers and providers, as a fundamental missing link to achieving impact. A new results framework for TVET is presented and maps the critical role of accountability as a feedback mechanism for keeping TVET provision relevant to the private sector

The Challenge of Service Delivery in TVET

To understand how services like TVET do or do not respond to the needs of citizens, one must first understand the concept of service delivery. A barber or a food vendor provides a service to the consumers of those services – haircuts and meals. When those services are delivered in a competitive market, the service provider will naturally care about (and be accountable to) the tastes and demands of their clients. Consumers exert client power over the seller when they decide whether or not to purchase a meal or pay for the service of a haircut, and more importantly whether or not to give them repeat business. The 2004 World Development Report (WDR) helpfully contrasts this competitive market client power with non-market services:Poor people—as patients in clinics, students in schools, travelers on buses, consumers of water—are the clients of services. They have a relationship with the frontline providers, with schoolteachers, doctors, bus drivers, water companies. [However, for those services…] there is no direct accountability of the provider to the consumer. Why not? For various good reasons, society has decided that the service will be provided not through a market transaction but through the government taking responsibility.[[World Bank. “Making Services Work for the Poor.” World Development Report 2004.]]

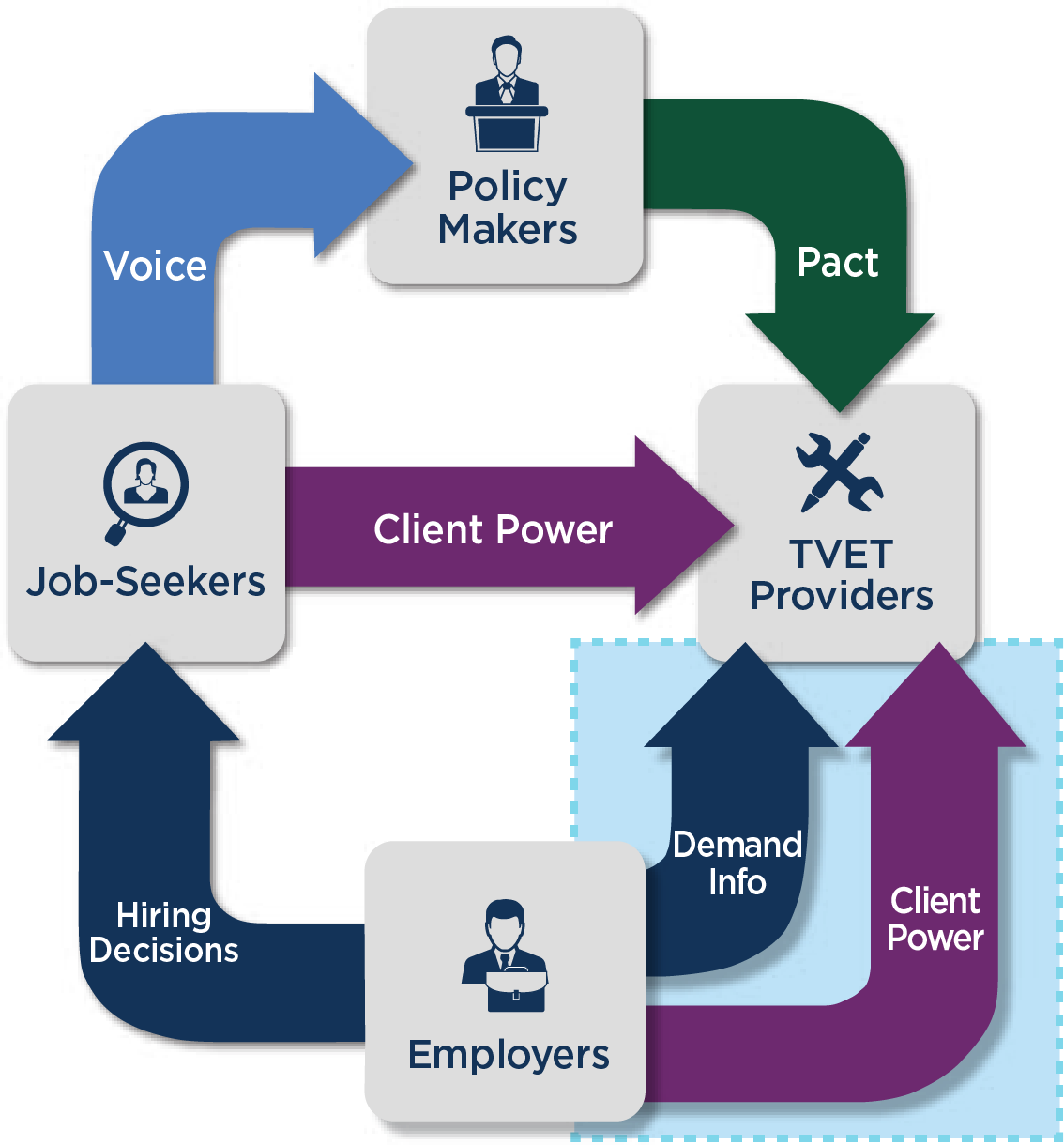

The WDR lays out an accountability framework which highlights two potential pathways through which public services respond to the needs of citizens, with an eye towards the poorest and most vulnerable. First is the short route of accountability in which service providers (i.e., nurses, teachers, or agricultural extension workers) are responsive to the client power of citizens as consumers of services. The long route of accountability traces how citizens can express their needs (voice) to the State, and the State in turn responds to their needs by creating a Pact[[The 2004 WDR model uses the term “compact” to describe the relationship between the state and providers. To avoid confusion with MCC’s Compact agreements, the term “Pact” is used instead.]] with providers. In other words, if service providers are to be responsive, either citizens can leverage their client power over providers or they can find ways to make politicians and policymakers responsive to citizens’ needs through their management and regulation of those providing services.

Accountability in TVET Service Delivery

The long and the short routes of accountability describe two pathways to make TVET providers responsive to the needs of jobseekers. Generally, skills and workforce development programs share some of the attractive textbook features of a market. There is free and fair exchange, enrollment and completion are a visible output of such an exchange, and there is always direct interaction between providers and their clients at the time of this “exchange”. Together, in theory, these features allow “clients” (i.e., jobseekers or others in search of skills) to have a degree of direct, or “short-route,” accountability over TVET providers.Figure 1: Accountability in TVET

Five Lessons for improved TVET programming

MCC’s TVET practice has yielded significant learning by bringing together the lessons from the First Generation of TVET programs with those emerging from the design and implementation of the Second Generation. Five key lessons have emerged from MCC’s TVET programming for the design and delivery of improved TVET. MCC will continue revisiting and updating its learning and approach based on new evaluation results as they become available.Lesson 1: A Demonstrated Skills Gap Should be a Precondition for Investment in TVET

MCC, governments, and other development partners should critically assess whether TVET is the right solution in a given context. MCC is working to ensure TVET investments are growth-enhancing by:- Continuing to invest in contexts where specific, demonstrable human capital gaps have been identified as a constraint to economic growth; and

- Focusing on areas where data demonstrates that employers have human capital needs that are not currently being produced by the existing system.

Lesson 2: TVET Should Have Two Primary Goals: Placing Graduates in Jobs with Improved Incomes and Supplying the Private Sector with In-Demand Skills

Governments and donors should begin with these results in mind and then should design reforms and interventions to achieve them. MCC’s new results framework (See Figure 2) can provide a road map to achieving impact: keep the end results in mind and focus on governance arrangements that create both short- and long-route accountability. Moreover, those mechanisms need to be flexible to account for the constant pace of technological change and changes in skills demand. Importantly, existing systems for public provision may not be capable of delivering the desired results. Innovative approaches to deliver TVET services are needed.Figure 2: MCC’s New Results Framework for TVET

Lesson 3: Focus First on Short-Route Accountability – Especially between Employers and Service Providers

The most direct way of increasing the accountability of service providers is via the short route – where providers receive direct feedback from firms (as their clients) on whether the training being provided is adequate and what new or evolving skills will be needed in the near future. This ensures that clients have voice and influence over providers. Achieving employer-provider accountability may require governments (and donors) to reassess traditional models of publicly delivered TVET.Public-private governance is one example of how to create short-route accountability to employers. Figure 3 shows how this can be achieved through the close alignment of firms and TVET providers. In one model in Morocco and Senegal, the actors are united by making the provider a subsidiary of an industry association. This creates direct client power between those associations and the training providers.

Figure 3: Creating Employer Client Power