Introduction

The Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) is an independent U.S. Government agency with the mission to reduce poverty in developing countries through enduring economic growth.

Each year, the MCC Board of Directors (Board) selects countries as eligible for MCC assistance. The selection process begins with the Board identifying candidate countries to consider by statute, which as of the date of publication, are all countries classified as either low income or lower middle income by the World Bank that are not prohibited from receiving assistance by federal law. For a candidate country to then be selected as eligible to receive assistance, it must demonstrate a commitment to ruling justly, investing in its people, and economic freedom as measured by independent policy indicators. These indicators inform the Board of candidate countries’ broad policy framework for encouraging poverty reduction through economic growth.

These indicators are compiled into country scorecards. This is a guide to understanding and interpreting the indicators used on the country scorecards by MCC in Fiscal Year 2025. It provides an overview of the policies measured by the indicators, the relationship that these policies have to economic growth and poverty reduction, the methodologies used by the various indicator institutions to measure policy performance, descriptions of the underlying source(s) of data, and the contact information of the indicator institutions. This document also provides the specific information for how MCC constructs the final indicators from these sources. The scorecards produced using these indicators are available at: https://www.mcc.gov/who-we-select/scorecards.

For general questions about the application of these indicators, please contact MCC’s Selection, Eligibility,and Policy Performance Division at DevelopmentPolicy@mcc.gov.

Indicators—What They Measure

The MCC scorecards measure performance on the policy criteria mandated in MCC’s authorizing legislation. By using information collected from independent third-party sources, MCC’s country selection process allows for an objective, comparable analysis across candidate countries.

MCC favors indicators that:

- are developed by an independent third party,

- use an analytically-rigorous methodology and objective, high-quality data,

- are publicly available,

- have broad country-coverage among MCC candidate countries,

- are comparable across countries,

- have a clear theoretical or empirical link to economic growth and poverty reduction,

- are policy-linked, (i.e. measure factors that governments can influence), and

- have appropriate consistency in results from year to year.

Ruling Justly

These indicators measure just and democratic governance, including a country’s demonstrated commitment to promoting political pluralism, equality, and the rule of law; respecting human and civil rights; protecting private property rights; encouraging transparency and accountability of government; and combating corruption.

- Political Rights – Independent experts rate countries on the prevalence of free and fair electoral processes; political pluralism and participation of all stakeholders; government accountability and transparency; freedom from domination by the military, foreign powers, totalitarian parties, religious hierarchies and economic oligarchies; and the political rights of minority groups, among other things. Source: Freedom House

- Civil Liberties – Independent experts rate countries on: freedom of expression; association and organizational rights; rule of law and human rights; and personal autonomy and economic rights, among other things. Source: Freedom House

- Control of Corruption – An index of surveys and expert assessments that rate countries on: “grand corruption” in the political arena; the frequency of petty corruption; the effects of corruption on the business environment; and the tendency of elites to engage in “state capture,” among other things. Source: World Bank/Brookings Institution’s Worldwide Governance Indicators

- Government Effectiveness – An index of surveys and expert assessments that rate countries on: the quality of public service provision; civil servants’ competency and independence from political pressures; and the government’s ability to plan and implement sound policies, among other things. Source: World Bank/Brookings Institution’s Worldwide Governance Indicators

- Rule of Law – An index of surveys and expert assessments that rate countries on: the extent to which the public has confidence in and abides by the rules of society; the incidence and impact of violent and nonviolent crime; the effectiveness, independence, and predictability of the judiciary; the protection of property rights; and the enforceability of contracts, among other things. Source: World Bank/Brookings Institution’s Worldwide Governance Indicators

- Freedom of Information – Measures the legal and practical steps taken by a government to enable or allow information to move freely through society; this includes measures of press freedom, national freedom of information laws, and the extent to which a country is shutting down the internet or social media. Source: Access Now / Centre for Law and Democracy / Reporters Without Borders

Investing in People

These indicators measure investments in the promotion of broad-based education, strengthened capacity to provide quality public health, the reduction of child mortality, and the management of natural resources.

- Immunization Rates – The average of DPT3 and measles immunization coverage rates for the most recent year available. Source: >WHO and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)

- Health Expenditures – Total expenditures on health by government (excluding funding sourced from external donors) at all levels divided by gross domestic product (GDP). Source: The World Health Organization (WHO)

- Education Expenditures – Total expenditures on education by government at all levels divided by GDP. Source: The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Institute of Statistics and National Governments

- Girls' Primary Education Completion Rate – The number of female students enrolled in the last grade of primary education minus repeaters divided by the population in the relevant age cohort (gross intake ratio in the last grade of primary). Countries with a GNI/capita of $2,165 or less are assessed on this indicator. Source: UNESCO Institute of Statistics and National Governments

- Girls’ Lower Secondary Education Completion Rate – The number of female pupils that have completed the last grade of lower secondary education divided by the population within three to five years of the intended age of completion, expressed as a percentage of the total population of females in the same age group. Countries with a GNI/capita between $2,166 and $4,515 are assessed on this indicator instead of Girls’ Primary Completion Rate. Source: UNESCO Institute of Statistics and National Governments

- Girls’ Upper Secondary Education Completion Rate – The number of female pupils that have completed the last grade of upper secondary education divided by the population within three to five years of the intended age of completion, expressed as a percentage of the total population of females in the same age group. Countries with a GNI/capita between $4,516 and $7,895 are assessed on this indicator instead of Girls’ Primary Completion Rate. Source: UNESCO Institute of Statistics and National Governments

- Child Health – An index made up of three indicators: access to improved water, access to improved sanitation, and child (ages 1-4) mortality. Source: The Center for International Earth Science Information Network and the Yale Center for Environmental Law and Policy

- Natural Resource Protection – Assesses a country government’s commitment to preserving biodiversity and natural habitats, responsibly managing ecosystems and fisheries, and engaging in agriculture that can be sustained. Source: Yale Center for Environmental Law and Policy

Encouraging Economic Freedom

These indicators measure the extent to which a government encourages economic freedom, including a demonstrated commitment to economic policies that: encourage individuals and firms to participate in global trade and international capital markets, promote private sector growth and strengthen market forces in the economy.

- Regulatory Quality – An index of surveys and expert assessments that rate countries on: the burden of regulations on business; price controls; the government’s role in the economy; and foreign investment regulation, among other areas. Source: World Bank/Brookings Institution’s Worldwide Governance Indicators

- Land Rights and Access – An index that rates countries on the extent to which the institutional, legal, and market framework provides secure land tenure and equitable access to land in rural areas and the extent to which men and women have the right to private property in practice and in law. Source: The International Fund for Agricultural Development and Varieties of Democracy Index

- Access to Credit – An index that ranks countries based on access and use of formal and informal financial services as measured by the number of bank branches and ATMs per 100,000 adults and the share of adults that have an account at a traditional financial institution or money market provider. Source: Financial Development Index (International Monetary Fund) and Findex (World Bank)

- Employment Opportunity: Measures a country government’s commitment to ending slavery and forced labor, preventing employment discrimination, and protecting the rights of workers and people with disabilities. Sources: Varieties of Democracy Institute and WORLD Policy Analysis Center (UCLA).

- Trade Policy: A measure of a country’s openness to international trade based on weighted average tariff rates and non-tariff barriers to trade. Source: The Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom

- Inflation – The most recent average annual change in consumer prices. Source: The International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) World Economic Outlook Database

- Fiscal Policy – General government net lending/borrowing as a percent of GDP, averaged over a three-year period. Net lending/borrowing is calculated as revenue minus total expenditure. Source: The IMF’s World Economic Outlook Database

- Women in the Economy – An index that measures the extent to which laws provide both men and women the ability to generate income or participate in the economy, including factors such as the capacity to access institutions, get a job, register a business, sign a contract, open a bank account, choose where to live, to travel freely, property rights protections, protections against domestic violence, and child marriage, among others. Source: Women, Business, and the Law (World Bank) and the WORLD Policy Analysis Center (UCLA)

- Inflation, on which a country’s inflation rate must be under a fixed ceiling of 15 percent;

- Immunization Rates, on which a country must have immunization coverage above 90% or the median, whichever is lower;

- Political Rights, on which countries must score above 17; and

- Civil Liberties, on which countries must score above 25.

- free and fair executive and legislative elections; fair polling; honest tabulation of ballots;

- fair electoral laws; equal campaigning opportunities;

- the right to organize in different political parties and political groupings; the openness of the political system to the rise and fall of competing political parties and groupings;

- the existence of a significant opposition vote; the existence of a de facto opposition power, and a realistic possibility for the opposition to increase its support or gain power through elections;

- the participation of cultural, ethnic, religious, or other minority groups in political life;

- freedom from domination by the military, foreign powers, totalitarian parties, religious hierarchies, economic oligarchies, or any other powerful group in making personal political choices; and

- the openness, transparency, and accountability of the government to its constituents between elections; freedom from pervasive government corruption; government policies that reflect the will of the people.

- freedom of cultural expression, religious institutions and expression, and academia;

- freedom of assembly and demonstration, of political organization and professional organization, and collective bargaining;

- independence of the media and the judiciary;

- freedom from economic exploitation;

- protection from police terror, unjustified imprisonment, exile, and torture;

- the existence of rule of law, personal property rights, and equal treatment under the law;

- freedom from indoctrination and excessive dependency on the state;

- equality of opportunity;

- freedom to choose where to travel, reside, and work;

- freedom to select a marriage partner and protection from domestic violence; and

- the existence of a legal framework to grant asylum or refugee status in accordance with international and regional conventions and system for refugee protection.

- The prevalence of grand corruption and petty corruption at all levels of government;

- The effect of corruption on the “attractiveness” of a country as a place to do business;

- The frequency of “irregular payments” associated with import and export permits, public contracts, public utilities, tax assessments, and judicial decisions;

- Nepotism, cronyism and patronage in the civil service;

- The estimated cost of bribery as a share of a company’s annual sales;

- The perceived involvement of elected officials, border officials, tax officials, judges, and magistrates in corruption;

- The strength and effectiveness of a government’s anti-corruption laws, policies, and institutions;

- The extent to which:

- processes are put in place for accountability and transparency in decision-making and disclosure of information at the local level;

- government authorities monitor the prevalence of corruption and implement sanctions transparently;

- conflict of interest and ethics rules for public servants are observed and enforced;

- the income and asset declarations of public officials are subject to verification and open to public and media scrutiny;

- senior government officials are immune from prosecution under the law for malfeasance;

- the government provides victims of corruption with adequate mechanisms to pursue their rights;

- the tax administrator implements effective internal audit systems to ensure the accountability of tax collection;

- the executive budget-making process is comprehensive and transparent and subject to meaningful legislative review and scrutiny;

- the government ensures transparency, open-bidding, and effective competition in the awarding of government contracts;

- there are legal and functional protections for whistleblowers, anti-corruption activists, and investigators;

- allegations of corruption at the national and local level are thoroughly investigated and prosecuted without prejudice;

- government is free from excessive bureaucratic regulations, registration requirements, and/or other controls that increase opportunities for corruption;

- citizens have a legal right to information about government operations and can obtain government documents at a nominal cost.

- competence of civil service; effective implementation of government decisions; and public service vulnerability to political pressure;

- ability to manage political alternations without drastic policy changes or interruptions in government services;

- flexibility, learning, and innovation within the political leadership; ability to coordinate conflicting objectives into coherent policies;

- the efficiency of revenue mobilization and budget management;

- the quality of transportation infrastructure, telecommunications, electricity supply, public health care provision, and public schools; the availability of online government services;

- policy consistency; the extent to which government commitments are honored by new governments;

- prevalence of red tape; the degree to which bureaucratic delays hinder business activity;

- existence of a taxpayer service and information program, and an efficient and effective appeals mechanism;

- the extent to which:

- effective coordination mechanisms ensure policy consistency across departmental boundaries, and administrative structures are organized along functional lines with little duplication;

- the business processes of government agencies are regularly reviewed to ensure efficiency of decision making and implementation;

- political leadership sets and maintains strategic priorities and the government effectively implements reforms;

- hiring and promotion within the government is based on merit and performance, and ethical standards prevail;

- the government wage bill is sustainable and does not crowd out spending required for public services; pay and benefit levels do not deter talented people from entering the public sector; flexibility (that is not abused) exists to pay more attractive wages in hard-to-fill positions;

- government revenues are generated by low-distortion taxes; import tariffs are low and relatively uniform, export rebate or duty drawbacks are functional; the tax base is broad and free of arbitrary exemptions; tax administration is effective and rule-based; and tax administration and compliance costs are low;

- policies and priorities are linked to the budget; multi-year expenditure projections are integrated into the budget formulation process, and reflect explicit costing of the implications of new policy initiatives; the budget is formulated through systematic consultations with spending ministries and the legislature, adhering to a fixed budget calendar; the budget classification system is comprehensive and consistent with international standards; and off-budget expenditures are kept to a minimum and handled transparently;

- the budget is implemented as planned, and actual expenditures deviate only slightly from planned levels;

- budget monitoring occurs throughout the year based on well-functioning management information systems; reconciliation of banking and fiscal records is practiced comprehensively, properly, and in a timely way;

- in-year fiscal reports and public accounts are prepared promptly and regularly and provide full and accurate data; the extent to which accounts are audited in a timely, professional and comprehensive manner, and appropriate action is taken on budget reports and audit findings.

- public confidence in the police force and judicial system; popular observance of the law; a tradition of law and order; strength and impartiality of the legal system;

- prevalence of petty crime, violent crime, and organized crime; foreign kidnappings; economic impact of crime on local businesses; prevalence of human trafficking; government commitment to combating human trafficking;

- the extent to which a well-functioning and accountable police force protects citizens and their property from crime and violence; when serious crimes do occur, the extent to which they are reported to the police and investigated;

- security of private property rights; protection of intellectual property; the accuracy and integrity of the property registry; whether citizens are protected from arbitrary and/or unjust deprivation of property;

- the enforceability of private contracts and government contracts;

- the existence of an institutional, legal, and market framework for secure land tenure; access to land among men and women; effective management of common property resources; equitable user-rights over water resources for agriculture and local participation in the management of water resources;

- the prevalence of tax evasion and insider trading; size of the informal economy;

- independence, effectiveness, predictability, and integrity of the judiciary; compliance with court rulings; legal recourse for challenging government actions; ability to sue the government through independent and impartial courts; willingness of citizens to accept legal adjudication over physical and illegal measures; government compliance with judicial decisions, which are not subject to change except through established procedures for judicial review;

- the independence of prosecutors from political direction and control;

- the existence of effective and democratic civilian state control of the police, military, and internal security forces through the judicial, legislative, and executive branches; the police, military, and internal security services respect human rights and are held accountable for any abuses of power;

- impartiality and nondiscrimination in the administration of justice; citizens are given a fair, public, and timely hearing by a competent, independent, and impartial tribunal; citizens have the right to independent counsel and those charged with serious felonies are provided access to independent counsel when it is beyond their means; low-cost means are available for pursuing small claims; citizens can pursue claims against the state without fear of retaliation;

- protection of judges and magistrates from interference by the executive and legislative branches; judges are appointed, promoted, and dismissed in a fair and unbiased manner; judges are appropriately trained to carry out justice in a fair and unbiased manner; members of the national-level judiciary must give reasons for their decisions; existence of a judicial ombudsman (or equivalent agency or mechanism) that can initiate investigations and impose penalties on offenders;

- law enforcement agencies are protected from political interference and have sufficient budgets to carry out their mandates; appointments to law enforcement agencies are made according to professional criteria; law enforcement officials are not immune from criminal proceedings;

- the existence of an independent reporting mechanism for citizens to complain about police actions; timeliness of government response to citizen complaints about police actions.

- Access to Improved Sanitation: Produced by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), this indicator measures the percentage of the population with access to facilities that hygienically separate human excreta from human, animal, and insect contact. Facilities such as sewers or septic tanks, pour-flush latrines and simple pit or ventilated improved pit latrines are assumed to be adequate, provided that they are not public and not shared with other households.

- Access to Improved Water: Produced by WHO and UNICEF, this indicator measures the percentage of the population with access to at least 20 liters of water per person per day from an “improved” source (household connections, public standpipes, boreholes, protected dug wells, protected springs, and rainwater collection) within one kilometer of the user's dwelling and with collection times of no more than 30 minutes.

- Child Mortality (Ages 1-4): Produced by the United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (IGME), this indicator measures the probability of dying between ages 1 and 4.

- prevalence of regulations and administrative requirements that impose a burden on business; ease of starting and closing a new business; ease of registering property;

- government intervention in the economy; the extent to which government subsidies keep uncompetitive industries alive;

- labor market policies; employment law provides for flexibility in hiring and firing; wage and price controls;

- the complexity and efficiency of the tax system; pro-investment tax policies;

- trade policy; the height of tariffs barriers; the number of tariff bands; the stability of tariff rates; the extent to which non-tariff barriers are used; the transparency and predictability of the trade regime;

- investment attractiveness; prevalence of bans or investment licensing requirements; financial regulations on foreign investment and capital; legal restrictions on ownership of business and equity by non-residents; foreign currency regulations; general uncertainty about regulation costs; legal regulation of financial institutions; the extent to which exchange rate policy hinders firm competitiveness;

- extensiveness of legal rules and effectiveness of legal regulations in the banking and securities sectors; costs of uncertain rules, laws, or government policies;

- the strength of the banking system; existence of barriers to entry in the banking sector; ease of access to capital markets; protection of domestic banks from foreign competition; whether interest rates are heavily-regulated; transfer costs associated with exporting capital;

- participation of the private sector in infrastructure projects; dominance of state-owned enterprises; openness of public sector contracts to foreign investors; the extent of market competition; effectiveness of competition and anti-trust policies and legislation;

- the existence of a policy, legal, and institutional framework that supports the development of a commercially-based, market-driven rural finance sector that is efficient, equitable, and accessible to low-income populations in rural areas;

- the adoption of an appropriate policy, legal, and regulatory framework to support the emergence and development of an efficient private rural business sector; the establishment of simple, fast and transparent procedures for establishing private agri-businesses;

- the existence of a policy, legal, and institutional framework that supports the development and liberalization of commercially-based agricultural markets (for inputs and produce) that operate in a liberalized and private sector-led, functionally efficient and equitable manner, and that are accessible to small farmers; and

- the extent to which:

- corporate governance laws encourage ownership and financial disclosure and protect shareholder rights, and are generally enforced;

- state intervention in the goods and land market is generally limited to regulation and/or legislation to smooth out market imperfections;

- the customs service is free of corruption, operates transparently, relies on risk management, processes duty collections, and refunds promptly; and

- trade laws, regulations, and guidelines are published, simplified, and rationalized.

- Access to Land: Produced by IFAD, this indicator assesses the extent to which the institutional, legal, and market framework provides secure land tenure and equitable access to land in rural areas. The sub components can be found at https://webapps.ifad.org/members/eb/121/docs/EB-2017-121-R-3.pdf IFAD’s operational staff base their assessments on a questionnaire and guideposts identifying the basis of each scoring level, available at https://webapps.ifad.org/members/gc/45/docs/GC-45-L-4-Add-1.pdf, https://webapps.ifad.org/members/gc/42/docs/GC-42-L-6.pdf or https://webapps.ifad.org/members/eb/125/docs/EB-2018-125-R-4-Add-1.pdf. Past datasets can be found in the documents of IFAD’s governing council https://webapps.ifad.org/members/gc.

- Property Rights (v2xcl-prpty): Produced by the Varieties of Democracy Institute (V-Dem), this index measures the rights to acquire, possess, inherit, and sell private property, including land. It measures both de jure limits on legal property rights, but also de facto limits that may come in the form of customary law, religious law, common practice, or social norms. This indicator is assessed separately for men and women, and then averaged together. V-Dem gathers these data by surveying experts and aggregating their answers into a single index. More information on V-Dem’s methodology can be found here https://www.v-dem.net/en/our-work/methods/.

- Normalized IFAD = (Number of countries scoring below Country X on IFAD’s raw data in the income group) ÷ (Number of Countries scoring equal to or greater than Country X on IFAD’s raw data in the income group + Number of countries scoring below Country X on IFAD’s raw data in the income group)

- Normalized Property Rights = (Number of countries scoring below Country X on V-Dem’s raw data in the income group) ÷ (Number of Countries scoring equal to or greater than Country X on V-Dem’s raw data in the income group + Number of countries scoring below Country X on V-Dem’s raw data in the income group)

- Financial Institution Access (IMF): MCC uses the Financial Institution Access indicator from the IMF’s Financial Development Index. This indicator has two sub indicators: the number of bank branches per 100,000 adults from the World Bank’s FinStats, and the number of ATMs per 100,000 adults from the IMF’s Financial Access Surveys.

- Share of adults with an account (Findex): From the World Bank’s Findex Database, MCC uses the share of the population (adults 15+) with an account. This survey counts both accounts with traditional financial institutions and mobile money.

- Normalized IMF = (Number of countries scoring below Country X on IMF’s raw data in the income group) ÷ (Number of Countries scoring equal to or greater than Country X on IMF’s raw data in the income group + Number of countries scoring below Country X on IMF’s raw data in the income group)

- Normalized Findex = (Number of countries scoring below Country X on Findex raw data in the income group) ÷ (Number of Countries scoring equal to or greater than Country X on Findex’s raw data in the income group + Number of countries scoring below Country X on Findex’s raw data in the income group)

- Average Disability Rights = (Number of questions where there is a guaranteed right)/7

- Average Employment Rights = (Number of questions where there is an employment protection in law)/12

- Normalized Sub-Component = (Number of countries scoring below Country X on Sub-Component data in the income group) ÷ (Number of Countries scoring equal to or greater than Country X on Sub-Component data in the income group + Number of countries scoring below Country X on Sub-Component data in the income group)

- Trade-weighted average tariff rate;

- Non-tariff barriers (NTBs) including, but not limited to: import licenses; trade quotas; production subsidies; anti-dumping, countervailing, and safeguard measures; government procurement procedures; local content requirements; excessive marking and labeling requirements; export assistance; export taxes and tax concessions; and corruption in the customs service.

- Mobility (WBL): These questions explore women’s legal access to physical mobility within a country. Studies show that legally sanctioned discrimination against women has a significant negative impact on a country’s economic growth, because it prevents a large portion of the population from fully participating in the economy, thus lowering the average ability of the workforce.89

- Workplace (WBL): These questions explore specific barriers to women’s opportunities in the workplace. Sexual harassment and violence in the workplace can undermine women’s economic empowerment by preventing employment and blocking access to other financial resources.90 Research shows that when women have access to employment, investment in children’s health, nutrition, and education often increases, promoting higher levels of human capital.91

- Pay (WBL): These questions look at barriers to women’s pay. Restrictions that limit the range of jobs that women can hold can lead to occupational segregation and confinement of women to low-paying sectors and activities.92 Many jobs prohibited for women are in highly paid industries, which can have implications for their earning potential. Further, when women are excluded from “male” jobs in the formal sector, an overcrowding can occur in the “female” informal job sector. This leads to a depression of wages for an otherwise productive group of workers.93 Increasing women’s participation in the workforce alone is insufficient for increased economic growth.94

- Marriage (WBL): These questions look at the rights of women in marriage including questions on domestic violence, and child marriage. Research shows the earnings of women in formal wage work who are exposed to severe partner violence are significantly lower than women who do not experience such violence.95

- Parenthood (WBL): These questions look at the availability of parental leave and the rights of pregnant women. Childcare and parental leave increase workforce participation leading to poverty reduction and increased economic growth.96

- Entrepreneurship (WBL): This area explores barriers to women’s ability to start businesses. When women receive fewer legal rights, the country’s potential labor force and potential pool of entrepreneurs decreases. Women’s ability to start businesses and create jobs is essential to increase economic growth and alleviate poverty.97

- Assets (WBL): This area analyzes women’s ability to own, control, and inherit property. Owning and having an equal say in their use of property not only increases women’s financial security; it is also associated with their increased bargaining power within the household.98

- Pension (WBL): This area examines questions of whether men and women have the same rights with respect to pensions, retirement, retirement age, and periods of absence from the workforce due to childcare. Having the same rights for pensions has been shown to reduce poverty, particularly for older women.99

- Child Marriage and Customary/Religious Law (WORLD Policy Analysis Center): This area deals with women’s constitutional rights, and the status of Child Marriage. Due to the typically large age differences between girls younger than 18 and their husbands, child brides lack bargaining power in the marriage and have less say over their activities and choices, including education and economic activity.100 Child marriage—through reduced decision-making power, greater likelihood of school dropout and illiteracy, lower labor force participation and earnings, and less control over productive household assets’severely impedes the economic opportunities of young women.101 For many women in rural areas, customary and religious law can override constitutional protections for equality and legal rights.102

- Afghanistan

- Angola

- Benin

- Burkina Faso

- Burundi

- Cambodia

- Cameroon

- Central African Republic

- Chad

- Comoros

- Congo, Dem. Rep.

- Eritrea

- Ethiopia

- Gambia, The

- Guinea

- Guinea-Bissau

- Haiti

- Kenya

- Korea, Dem. People's Rep.

- Kyrgyz Republic

- Lao PDR

- Lesotho

- Liberia

- Madagascar

- Malawi

- Mali

- Mauritania

- Mozambique

- Myanmar

- Nepal

- Niger

- Nigeria

- Pakistan

- Rwanda

- Senegal

- Sierra Leone

- Somalia

- South Sudan

- Sudan

- Syrian Arab Republic

- Tajikistan

- Tanzania

- Timor-Leste

- Togo

- Uganda

- Yemen, Rep.

- Zambia

- Zimbabwe

- Bangladesh

- Bhutan

- Bolivia

- Cabo Verde

- Congo, Rep.

- Côte d'Ivoire

- Djibouti

- Egypt, Arab Rep.

- Eswatini

- Ghana

- Honduras

- India

- Jordan

- Kiribati

- Lebanon

- Micronesia, Fed. Sts.

- Morocco

- Nicaragua

- Papua New Guinea

- Philippines

- Samoa

- São Tomé and Principe

- Solomon Islands

- Sri Lanka

- Tunisia

- Uzbekistan

- Vanuatu

- Vietnam

- Albania

- Algeria

- Armenia

- Azerbaijan

- Belarus

- Belize

- Botswana

- Colombia

- Ecuador

- El Salvador

- Equatorial Guinea

- Fiji

- Georgia

- Guatemala

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Iraq

- Jamaica

- Kosovo

- Libya

- Marshall Islands

- Moldova

- Mongolia

- Namibia

- North Macedonia

- Paraguay

- Peru

- South Africa

- Suriname

- Thailand

- Tonga

- Tuvalu

- Ukraine

Determining MCC Candidacy

For Fiscal Year 2025 (FY25), 76 countries meet the income parameters for MCC candidacy (with 62 being candidates and 14 meeting the income parameters but that are statutorily prohibited from receiving assistance). MCC creates scorecards for all 76 countries that meet the income parameters. A country is determined to be an MCC candidate if its per capita income falls within predetermined parameters set by Congress, and it is not subject to certain restriction on U.S. foreign assistance. Those parameters are that the country must be classified as either low income or lower middle income by the World Bank (which means it is estimated to have a Gross National Income (GNI) per capita (Atlas Method) less than the World Bank’s lower middle income country threshold of $4,515 in FY25, as published in the World Bank’s July release of income data.1

Legislation known as the Millennium Challenge Corporation Candidate Country Reform Act is under active consideration by the United States Congress. If passed as currently drafted, the legislation would reform the income threshold for countries to be candidate countries for purposes of eligibility for MCC assistance by changing it to the World Bank threshold for initiating the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development graduation process for the fiscal year ($7,895 gross national income per capita for FY 2025). This would mean that 109 countries would meet the new income parameters (with 92 being candidates and 17 meeting the income parameters by that are statutorily prohibited from receiving assistance). See the FY25 Candidate Country Report for additional information.

Setting the Scorecard Income Groups

For FY25, MCC is continuing to use the historical ceiling for eligibility as set by the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA) (often referred to as the ‘Historical IDA Threshold’) to divide the 76 countries into two income groups for the purpose of comparative analysis on the scorecard policy performance indicators. These two income groups are: 1) countries whose GNI per capita is less than or equal to $2,165 in FY25 and 2) those countries whose GNI per capita falls between $2,166 and $4,515 in FY25.

If the Millennium Challenge Corporation Candidate Country Reform Act is passed as currently drafted, MCC will create a third scorecard income group comprised of countries whose GNI per capita falls between $4,516 and $7,895 in FY25. A full list of the countries in each income pool can be found in the Notes section of this document. For additional information, see the FY25 Selection Criteria and Methodology Report.

Indicator Performance

A country is considered to “pass” a given indicator if it performs better than the median score in its income group or the absolute threshold (for certain indicators – see below). A country is considered to “pass” the scorecard if it: (i) “passes” at least ten of the 20 indicators, with at least one pass in each of the three categories; (ii) “passes” the Control of Corruption indicator; and, (iii) “passes” either the Civil Liberties or Political Rights indicator. For technical specifics regarding how these medians are calculated see the Note on Calculating Medians at the end of this document. Indicators with absolute thresholds in lieu of a median include:

The Board also takes into consideration whether a country performs substantially worse in any category (Ruling Justly, Investing in People, or Economic Freedom) than it does on the overall scorecard. While the indicator methodology is the predominant basis for determining which countries will be eligible for assistance, the Board also considers supplemental information and takes into account factors such as time lags and gaps in the data used to determine indicator scores.

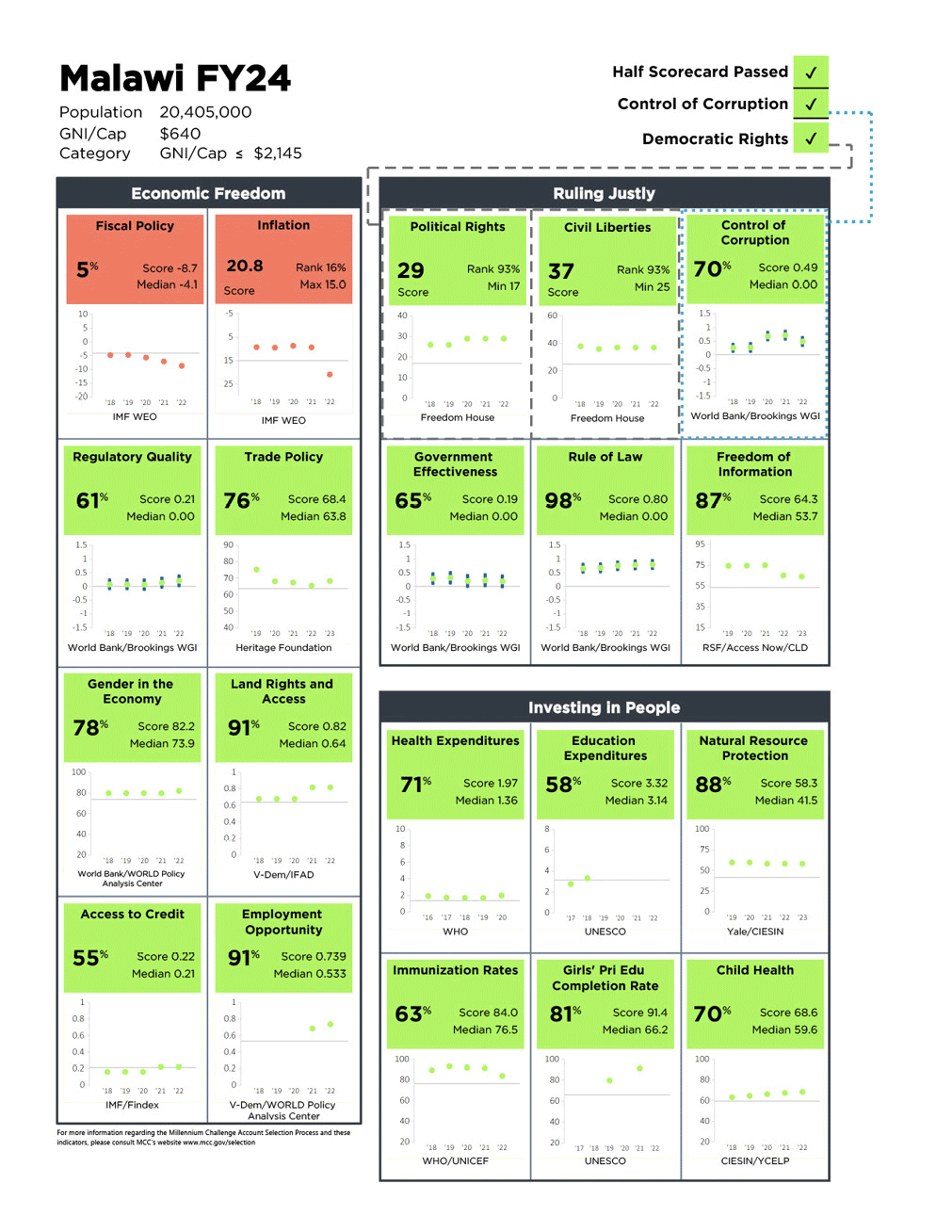

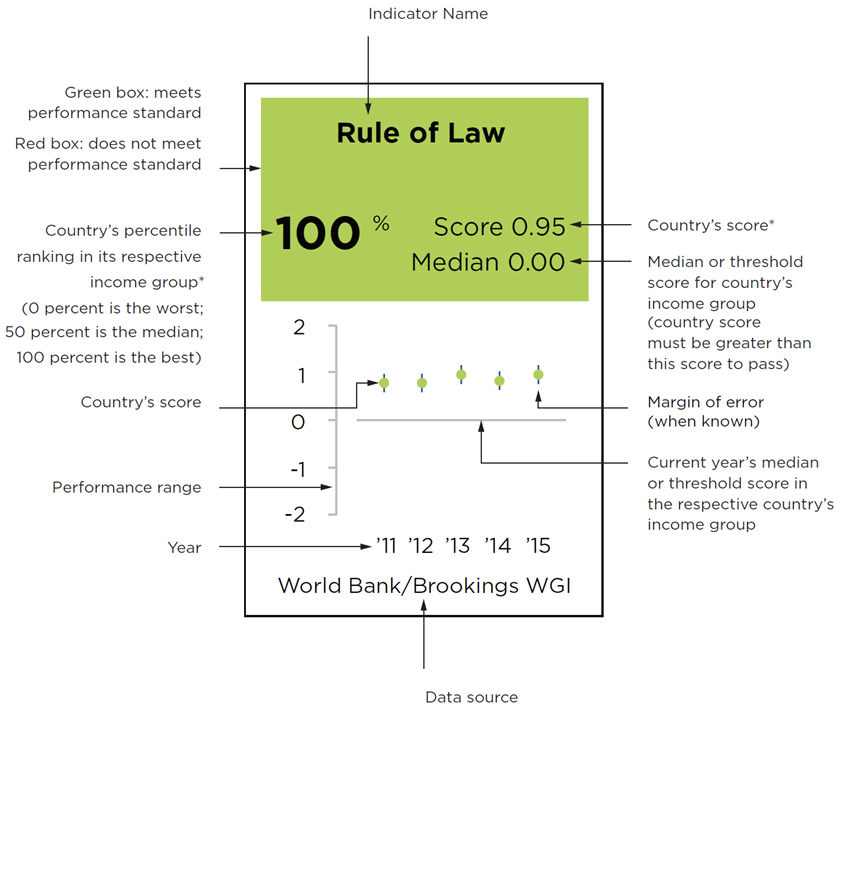

Example Scorecard:

For reference, this is an example of a scorecard from FY24 and a guide for reading each of the indicators.

Reading the Indicators

Every year each MCC candidate country receives a scorecard assessing performance in three policy categories: Ruling Justly, Investing in People, and Encouraging Economic Freedom.

*For the Political Rights, Civil Liberties, Inflation, and Immunization Rates (when the median is over 90% immunized) indicators, the score and percent ranking are reversed due to those indicators operating on a minimum or maximum-score system rather than a median based system.

Ruling Justly Category

The six indicators in this category measure just and democratic governance by assessing, among other things, a country’s demonstrated commitment to promote political pluralism, equality, and the rule of law; respect human and civil rights, including the rights of people with disabilities; protect private property rights; encourage transparency and accountability of government; and combat corruption.

Political Rights Indicator

This indicator measures country performance on the quality of the electoral process, political pluralism and participation, government corruption and transparency, and fair political treatment of ethnic groups.

Countries are rated on the following factors:

Relationship to Growth and Poverty Reduction

Although the relationship between democracy and economic growth is complex, research suggests that the institutional structures of democracy can promote growth by increasing policy stability, cultivating higher rates of human capital accumulation, reducing levels of income inequality and corruption, and encouraging higher rates of investment.2 The links between political rights and poverty reduction are similarly complicated, but there is evidence that democratic institutions are better at reducing economic volatility and provide a more consistent approach to poverty reduction than do autocratic regimes.3 Research also links the incentive structure of democratic institutions with outcomes favorable for the poor.4

Source

Freedom House, http://www.freedomhouse.org. Questions regarding this indicator may be directed to info@freedomhouse.org or +1 (212) 514-8040.

Indicator Institution Methodology

The Political Rights indicator is based on a team of expert analysts and scholars evaluating countries using a ten question checklist grouped into the three subcategories: Electoral Process (3 questions), Political Pluralism and Participation (4 questions), and Functioning of Government (3 questions). Points are awarded to each question on a scale of 0 to 4, where 0 points represents the fewest rights and 4 represents the most rights. The highest number of points that can be awarded to the Political Rights checklist is 40 (or a total of up to 4 points for each of the 10 questions). There is also an additional, discretionary, political rights question which can subtract up to 4 points from a country’s score. The full list of questions included in Freedom House’s methodology may be found at: https://freedomhouse.org/reports/freedom-world/freedom-world-research-methodology.

In consultation with Freedom House, MCC considers countries with scores above 17 to be passing this indicator.

MCC Methodology

Freedom House publishes a 1-7 scale (where 7 is “least free” and 1 is “most free”) for Political Rights. Since its Freedom in the World 2006 report, Freedom House has also released data using a 0-40 scale for Political Rights (where 0 is “least free” and 40 is “most free”). Table 1 illustrates how the 1-7 scale used prior to Fiscal Year 2007 (FY07) corresponds to the new 0-40 scale.

| New Scale | Old Scale |

|---|---|

| 36-40 | 1 |

| 30-35 | 2 |

| 24-29 | 3 |

| 18-23 | 4 |

| 12-17 | 5 |

| 6-11 | 6 |

| 0-5 | 7 |

MCC adjusts the years on the x-axis of the Country Scorecards to correspond to the period of time covered by the Freedom in the World publication. For instance, FY25 Political Rights data come from Freedom in the World 2024 and are labeled as 2023 data on the scorecard (the year Freedom House is reporting on in its 2024 report.)

Civil Liberties Indicator

This indicator measures country performance on freedom of expression and belief, associational and organizational rights, rule of law and human rights, personal autonomy, individual and economic rights, and the independence of the judiciary.

Countries are rated on the following factors:

Relationship to Growth and Poverty Reduction:

Studies show that an expansion of civil liberties can promote economic growth by reducing social conflict, removing legal impediments to participation in the economy, encouraging adherence to the rule of law, enhancing protection of property rights, increasing economic rates of return on government projects, and reducing the risk of project failure.5 Additional research has shown that civil liberties have a positive effect on domestic investment and productivity, increase the success of investments by international actors, enhance economic freedoms, and can bolster growth through the freedom of mobility for individuals.6

Source

Freedom House, http:/www./freedomhouse.org. Questions regarding this indicator may be directed to info@freedomhouse.org or +1 (212) 514-8040.

Indicator Institution Methodology

A team of expert analysts and scholars evaluate countries on a 60-point scale – with 60 representing “most free” and 0 representing “least free.” The Civil Liberties indicator is based on a 15 question checklist grouped into four subcategories: Freedom of Expression and Belief (4 questions), Associational and Organizational Rights (3 questions), Rule of Law (4 questions), and Personal Autonomy and Individual Rights (4 questions). Points are awarded to each question on a scale of 0 to 4, where 0 points represents the fewest liberties and 4 represents the most liberties. The highest number of points that can be awarded to the Civil Liberties checklist is 60 (or a total of up to 4 points for each of the 15 questions). The full list of questions included in Freedom House’s methodology may be found at: https://freedomhouse.org/reports/freedom-world/freedom-world-research-methodology.

In consultation with Freedom House, MCC considers countries with scores above 25 to be passing this indicator.

MCC Methodology

Freedom House publishes a 1-7 scale (where 7 is “least free” and 1 is “most free”) for Civil Liberties. Since its Freedom in the World 2006 report, Freedom House has also released data using a 0-60 scale (where 0 is “least free” and 60 is “most free”) for Civil Liberties. Table 2 illustrates how the 1-7 scale used prior to FY07 corresponds to the new 0-60 scale.

| New Scale | Old Scale |

|---|---|

| 53-60 | 1 |

| 44-52 | 2 |

| 35-43 | 3 |

| 26-34 | 4 |

| 17-25 | 5 |

| 8-16 | 6 |

| 0-7 | 7 |

MCC adjusts the years on the x-axis of the Country Scorecards to correspond to the period of time covered by the Freedom in the World publication. For instance, FY25 Civil Liberties data come from Freedom in the World 2024 and are labeled as 2023 data on the scorecard (the year Freedom House is reporting on in its 2024 report).

Control of Corruption Indicator

This indicator measures the extent to which public power is exercised for private grain, including both petty and grand forms of corruption, as well as “capture” of the state by elites and private interests. It also measures the strength and effectiveness of a country’s policy and institutional framework to prevent and combat corruption.

Countries are evaluated on the following factors:

Relationship to Growth and Poverty Reduction

Corruption hinders economic growth by increasing costs, lowering productivity, discouraging investment, reducing confidence in public institutions, limiting the development of small and medium-sized enterprises, weakening systems of public financial management, and undermining investments in health and education.7 Corruption can also increase poverty by slowing economic growth, skewing government expenditure in favor of the rich and well-connected, concentrating public investment in unproductive projects, promoting a more regressive tax system, siphoning funds away from essential public services, adding a higher level of risk to the investment decisions of low-income individuals, and reinforcing patterns of unequal asset ownership, thereby limiting the ability of the poor to borrow and increase their income.8

Source

Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) from the World Bank/Brookings Institution, http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/. Questions regarding this indicator may be directed to wgi@worldbank.org or +1 (202) 473-4557.

Indicator Institution Methodology

The indicator is an index combining a subset of 24 different assessments and surveys, depending on availability, each of which receives a different weight, depending on its estimated precision and country coverage. The Control of Corruption indicator draws on data, as applicable, from the Country Policy and Institutional Assessments of the World Bank, the African Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the Afrobarometer Survey, the World Bank’s Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Survey, the Bertelsmann Foundation’s Bertelsmann Transformation Index, the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Country Risk Service, The University of Gothenburg’s European Quality of Government Index, Transparency International’s Global Corruption Barometer survey, the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report, Global Integrity’s African Integrity Index (previously known as the Global Integrity Index), the Gallup World Poll, Freedom House’s Nation in Transit, Freedom House’s Countries at the Crossroads, the International Fund for Agricultural Development’s Rural Sector Performance Assessments, Political Economic Risk Consultancy’s Corruption in Asia, Political Risk Service’s International Country Risk Guide, Vanderbilt University Americas Barometer Survey, the Institute for Management and Development’s World Competitiveness Yearbook, Varieties of Democracy’s Corruption Index, the French Government’s Institutional Profiles Database, IHS Markit’s World Economic Service, the World Bank's Enterprise Surveys, and the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index.

MCC Methodology

MCC Normalized Score = WGI Score - median score

For ease of interpretation, MCC has adjusted the median for each of the two scorecard income pools to zero for all of the Worldwide Governance Indicators. Country scores are calculated by taking the difference between actual scores and the median. For example, in FY24 the unadjusted median for the scorecard category of countries with a Gross National Income (GNI) per capita between $2,146 and $4,465 on Control of Corruption was -0.54 (note, in FY25, the GNI per capita range for this scorecard category is $2,166 to $4,515). In order to set the median at zero, MCC simply adds 0.54 to each country’s score (the same thing as subtracting a negative 0.54). Therefore, as an example, Algeria’s FY24 Control of Corruption score, which was originally -0.64, was adjusted to -0.10.

The FY25 scores come from the 2024 update of the Worldwide Governance Indicators dataset and largely reflect performance in calendar year 2023. Since the release of the 2006 update of the Worldwide Governance Indicators, the indicators are updated annually. Each year, the World Bank and Brookings Institution also make minor backward revisions to the historical data. Prior to 2006, the World Bank released data every two years (1996, 1998, 2000, 2002 and 2004). With the 2006 release, the World Bank moved to an annual reporting cycle and provided additional historical data for 2003 and 2005.

Government Effectiveness Indicator

This indicator measures the quality of public services, the quality of the civil service and its independence from political pressures, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of the government’s commitment to its stated policies.

Countries are evaluated on the following factors:

Relationship to Growth and Poverty Reduction

Countries with more effective governments tend to achieve higher levels of economic growth by obtaining better credit ratings and attracting more investment, offering higher quality public services and encouraging higher levels of human capital accumulation, putting foreign aid resources to better use, accelerating technological innovation, and increasing the productivity of government spending.9 Efficiency in the delivery of public services also has a direct impact on poverty.10 On average, countries with more effective governments have better educational systems and more efficient health care.11 There is evidence that countries with independent, meritocratic bureaucracies do a better job of vaccinating children, protecting the most vulnerable members of society, reducing child mortality, and curbing environmental degradation.12 Countries with a meritocratic civil service also tend to have lower levels of corruption.13

Source

Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) from the World Bank/Brookings Institution, http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/. Questions regarding this indicator may be directed to wgi@worldbank.org or +1 (202) 473-4557.

Indicator Institution Methodology

The indicator is an index combining a subset of 18 different assessments and surveys, depending on availability, each of which receives a different weight, depending on its estimated precision and country coverage. The Government Effectiveness indicator draws on data, as applicable, from the Country Policy and Institutional Assessments of the World Bank, the African Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the Afrobarometer Survey, the World Bank’s Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Survey, the Bertelsmann Foundation’s Bertelsmann Transformation Index, Global Integrity’s African Integrity Index (previously known as the Global Integrity Index), the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Country Risk Service, The University of Gothenburg’s European Quality of Government Index, the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report, the Gallup World Poll, the International Fund for Agricultural Development’s Rural Sector Performance Assessments, the Latinobarometro Survey, Political Risk Service’s International Country Risk Guide, the French Government’s Institutional Profiles Database, IHS Markit’s World Economic Service, the World Bank's Enterprise Surveys, and the Institute for Management and Development’s World Competitiveness Yearbook.

MCC Methodology

MCC Normalized Score = WGI Score - median score

For ease of interpretation, MCC has adjusted the median for each of the two scorecard income pools to zero for all of the Worldwide Governance Indicators. Country scores are calculated by taking the difference between actual scores and the median. For example, in FY24 the unadjusted median for the scorecard category of countries with a Gross National Income (GNI) per capita between $2,146 and $4,465 on Control of Corruption was -0.54 (note, in FY25, the GNI per capita range for this scorecard category is $2,166 to $4,515). In order to set the median at zero, MCC simply adds 0.54 to each country’s score (the same thing as subtracting a negative 0.54). Therefore, as an example, Algeria’s FY24 Control of Corruption score, which was originally -0.64, was adjusted to -0.10.

The FY25 scores come from the 2024 update of the Worldwide Governance Indicators dataset and largely reflect performance in calendar year 2023. Since the release of the 2006 update of the Worldwide Governance Indicators, the indicators are updated annually. Each year, the World Bank and Brookings Institution also make minor backward revisions to the historical data. Prior to 2006, the World Bank released data every two years (1996, 1998, 2000, 2002 and 2004). With the 2006 release, the World Bank moved to an annual reporting cycle and provided additional historical data for 2003 and 2005.

Rule of Law Indicator

This indicator measures the extent to which individuals and firms have confidence in and abide by the rules of society; in particular, it measures the functioning and independence of the judiciary, including the police, the protection of property rights, the quality of contract enforcement, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence.

Countries are evaluated on the following factors:

Relationship to Growth and Poverty Reduction

Judicial independence is strongly linked to growth as it promotes a stable investment environment.14 On average, business environments characterized by consistent policies and credible rules, such as secure property rights and contract enforceability, create higher levels of investment and growth.15 Secure property rights and contract enforceability also have a positive impact on poverty by granting citizens secure rights to their own assets.16 Research shows that people who do not have the resources or the connections to protect their rights informally are usually in most need of formal protection through efficient legal systems.17

Source

Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) from the World Bank/Brookings Institution, http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/. Questions regarding this indicator may be directed to wgi@worldbank.org or +1 (202) 473-4557.

Indicator Institution Methodology

The indicator is an index combining a subset of 24 different assessments and surveys, depending on availability, each of which receives a different weight, depending on its estimated precision and country coverage. The Rule of Law indicator draws on data, as applicable, the Country Policy and Institutional Assessments of the World Bank, the African Development Bank and the Asian Development Bank, the Afrobarometer Survey, the World Bank’s Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Survey, the Bertelsmann Foundation’s Bertelsmann Transformation Index, Freedom House’s Nations in Transit report, Freedom House’s Countries at the Crossroads report, the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Country Risk Service, The University of Gothenburg’s European Quality of Government Index, the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report, Global Integrity’s African Integrity Index (previously known as the Global Integrity Index), the Gallup World Poll, the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom, the International Fund for Agricultural Development’s Rural Sector Performance Assessments, the Latinobarometro Survey, Political Risk Service’s International Country Risk Guide, the United States State Department’s Trafficking in Persons Report, Vanderbilt University’s Americas Barometer, Institute for Management and Development’s World Competitiveness Yearbook, Varieties of Democracy’s Liberal Component Index, the French Government’s Institutional Profiles database, the World Bank's Enterprise Surveys, IHS Markit’s World Economic Service, and the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index.

MCC Methodology

MCC Normalized Score = WGI Score - median score

For ease of interpretation, MCC has adjusted the median for each of the two scorecard income pools to zero for all of the Worldwide Governance Indicators. Country scores are calculated by taking the difference between actual scores and the median. For example, in FY24 the unadjusted median for the scorecard category of countries with a Gross National Income (GNI) per capita between $2,146 and $4,465 on Control of Corruption was -0.54 (note, in FY25, the GNI per capita range for this scorecard category is $2,166 to $4,515). In order to set the median at zero, MCC simply adds 0.54 to each country’s score (the same thing as subtracting a negative 0.54). Therefore, as an example, Algeria’s FY24 Control of Corruption score, which was originally -0.64, was adjusted to -0.10.

The FY25 scores come from the 2024 update of the Worldwide Governance Indicators dataset and largely reflect performance in calendar year 2023. Since the release of the 2006 update of the Worldwide Governance Indicators, the indicators are updated annually. Each year, the World Bank and Brookings Institution also make minor backward revisions to the historical data. Prior to 2006, the World Bank released data every two years (1996, 1998, 2000, 2002 and 2004). With the 2006 release, the World Bank moved to an annual reporting cycle and provided additional historical data for 2003 and 2005.

Freedom of Information Indicator

This indicator measures a government’s commitment to enable or allow information to move freely in society. It is a composite index that includes a measure of press freedom; the status of national freedom of information laws; and a measure of internet filtering.

Relationship to Growth and Poverty Reduction

Governments play a role in information flows; they can restrict or facilitate information flows within countries or across borders. Many of the institutions (laws, regulations, codes of conduct) that governments design are created to manage the flow of information in an economy.18 Countries with better information flows often have better quality governance and less corruption.19 Higher transparency and access to information have been shown to increase investment inflows because they enhance an investor’s knowledge of the behaviors and operations of institutions in a target economy; help reduce uncertainty about future changes in policies and administrative practices; contribute data and perspectives on how best an investment project can be initiated and managed; and allow for the increased coordination between social and political actors that typifies successful economic development.20 The right of access to information within government institutions also strengthens government accountability, promotes political participation of all, reduces governmental abuses, and leads to more effective allocation of natural resources.21 Access to information also empowers those living in poverty by giving them the ability to more fully participate in society and providing them with knowledge that can be used for economic gain.22 Internet shutdowns are harmful as they not only restrict the ability of civil society to engage in political participation and government oversight, but also restrict market access and cost economies billions of dollars each year.23

Sources and Indicator Institution Methodologies

I. Reports without Borders’ (RSF) World Press Freedom Index, https://rsf.org/en/ranking/2020. Questions regarding this indicator may be directed to index@rsf.org or +33 1 44 83 84 65

World Press Freedom Index methodology: RSF compiles its data by pooling experts’ responses to 117 questions related to the political context, legal framework, economic situation, sociocultural context, and safety environment that face journalists in a country. This qualitative analysis is combined with quantitative data on abuses and acts of violence against journalists during the period evaluated.

II. Centre for Law and Democracy and Access Info’s Right to Information Index, http://www.rti-rating.org/. Questions regarding this indicator may be directed to Toby Mendel at toby@law-democracy.org or +1 (902) 431-3688.

Right to Information Methodology: In this dataset, a freedom of information law is rated based on 61 indicators. RTI includes any country with a freedom of information law on the books.

Access Now’s #KeepItOn Shutdown Tracker Optimization Project, https://www.accessnow.org/keepiton/. Questions regarding this indicator may be directed to Peter Micek at peter@accessnow.org or +1 (888) 414-0100.

Access Now Methodology: Countries are assigned one point for every day of internet or social media shutdown/throttling up to 9 days. Shutdowns listed as ongoing are assumed to last until the end of the year. Shutdowns that last less than one day are counted as one day. Shutdowns with no end date are assumed to only last one day. If no duration is listed, but a start and end date are listed, a duration is calculated. Non-government shutdowns and non-government throttlings are excluded.

MCC Methodology

MCC FOI Score = (Press) + (FOIA in place) - (Access Now)

This indicator uses a country’s score on RSF’s World Press Freedom Index (Press) as the base. In FY25, MCC uses RSF’s 2024 World Press Freedom Index, which covers events in 2023. A country’s base score may improve based on data from the Global Right to Information Rating. In FY25, MCC uses Centre for Law and Democracy / Access Info Europe’s Global Right to Information Rating (RTI) from 2023. A country’s score is improved by 4 points if they have a Freedom of Information law enacted. Data from Access Now is used to penalize some countries’ base scores. A country’s score is penalized 1 point for each day in the last calendar year (2023) of internet or social media shutdown/throttling, for a total penalty of up to 9 points. For FY25, MCC uses Access Now data from the 2025 #KeepItOn Shutdown Tracker Optimization Project report.

Note regarding construction of missing data: Prior to FY23, MCC utilized old data from Freedom House on Freedom of the Press to construct data for countries that were missing data from RSF. Starting in FY23, MCC will no longer use this methodology as RSF’s methodology has changed and it is no longer comparable to the old Freedom House data. Countries that are missing RSF data will be considered missing and therefore fail this indicator.

Investing in People Category

The indicators in this category measure investments in people by assessing the extent to which governments are promoting broad-based primary education, strengthening capacity to provide quality public health, increasing child health, and promoting the protection of biodiversity.

Immunization Rates Indicator

This indicator measures a government’s commitment to providing essential public health services and reducing child mortality.

Relationship to Growth and Poverty Reduction

The Immunization Rates indicator is widely regarded as a good proxy for the overall strength of a government’s public health system.24 It is designed to measure the extent to which governments are investing in the health and well-being of their citizens. Immunization programs can impact economic growth through their broader impact on health.25 Healthy workers are more economically productive and more likely to save and invest; healthy children are more likely to reach higher levels of educational attainment; and healthy parents are better able to invest in the health and education of their children.26 Immunization programs also increase labor productivity among the poor, reduce spending to cope with illnesses, and lower mortality and morbidity among the main income-earners in poor families.27

Source

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), http://www.who.int/immunization_monitoring/data/. Questions regarding this indicator may be directed to vaccines@who.int or +41 22 791 2873.

Indicator Institution Methodology

MCC uses the simple average of the national diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus (DPT3) vaccination rate and the measles (MCV) vaccination rate. The DPT3 immunization rate is measured as the number of children that have received their third dose of the diphtheria, pertussis (whooping cough), and tetanus toxoid vaccine divided by the target population (the number of children surviving their first year of life.) The measles immunization rate is measured as the number of children that have received their first dose of a measles-containing vaccine divided by the same target population.

To estimate national immunization coverage, WHO and UNICEF draw on two sources of empirical data: reports of vaccinations performed by service providers (administrative data) and surveys containing items on children’s vaccination history (coverage surveys). Surveys are frequently used in conjunction with administrative data; in some instances—where administrative data differ substantially from survey results’—surveys constitute the sole source of information on immunization coverage levels. There are a number of reasons survey data may be used over administrative data; for instance, in some cases, lack of precise information on the size of the target population (the denominator) can make immunization coverage difficult to estimate from administrative data alone. Estimates of the most likely true level of immunization coverage are based on the data available, consideration of potential biases, and contributions of local experts.

In consultation with the WHO, MCC considers countries which have immunization coverage above the median for their scorecard income pool to be passing this indicator. If the median is above 90% for an income pool in a year, countries in that income pool will be considered passing if they have immunization coverage above 90% (even if they score below the median).28

MCC Methodology

MCC Immunization Rate = [0.5 x DPT3 ] + [0.5 x MCV1]

MCC relies on official WHO/United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) estimates for all immunization data. MCC uses the simple average of the 2023 DPT3 coverage rate and the 2023 measles (MCV) coverage rate to calculate FY25 country scores. If a country is missing data for either DPT3 or Measles, it does not receive an index value. The same rule is applied to historical data. As better data become available, WHO/UNICEF make backward revisions to the historical data. In FY25, countries must have immunization rates (as defined above) greater than 90% or the median for their scorecard pool, whichever is lower, to pass this indicator.

Health Expenditures Indicator

This indicator measures the government’s commitment to investing in the health and well-being of its people.

Relationship to Growth and Poverty Reduction

MCC generally strives to measure outcomes rather than inputs, but health outcomes can be very slow to adjust to policy changes. Therefore, the Health Expenditures indicator is used to gauge the extent to which governments are making investments in the health and well-being of their citizens.29 A large body of literature links improved health outcomes to economic growth and poverty reduction.30 While the link between expenditures and outcomes is never automatic in any country, it is generally positive when expenditures are managed and executed efficiently.31 Research suggests that increased spending on health, when coupled with good policies and good governance, can promote growth, reduce poverty, and trigger declines in infant, child, and maternal mortality.32

Source

World Health Organization (WHO), http://www.who.int/nha/en/. Questions regarding this indicator may be directed to nhaweb@who.int.

Indicator Institution Methodology

This indicator measures domestic general government health expenditure (GGHE-D) as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Domestic general government health expenditure includes outlays earmarked for health maintenance, restoration or enhancement of the health status of the population, paid for in cash or in kind by the following financing agents: central/federal, state/provincial/regional, and local/municipal authorities; extra-budgetary agencies, social security schemes; and parastatals. All are financed through domestic funds. GGHE-D includes only current expenditures made during the year (excluding investment expenditures such as capital transfers). The classification of the functions of government (COFOG) promoted by the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), OECD and other institutions sets the boundaries for public outlays. Figures are originally estimated in million national currency units (million NCU) and in current prices. GDP data are primarily drawn from the United Nations National Accounts statistics.

MCC Methodology

This indicator measures public expenditure on health as a percent of gross domestic product (GDP). MCC relies on the World Health Organization (WHO) for data on public health expenditure. The WHO estimates domestic general government health expenditure (GGHE-D) — the sum of current outlays by government entities to purchase health care services and goods — in million national currency units (million NCU) and in current prices. GDP data are primarily drawn from the United Nations National Accounts statistics.

Prior to FY19, MCC utilized a slightly different indicator, which was discontinued by the WHO. Because MCC started using a different indicator from the WHO in FY19, data from FY19 onward on MCC’s scorecard are not comparable to data found on MCC scorecards prior to FY19.

The FY25 scores come from the 2024 update of the global health expenditure database and largely reflect performance in calendar year 2021. To ensure comparability, given the unprecedented nature of health spending in 2021, for FY25, MCC uses data from 2021 for all countries, even in the very few of cases where 2022 data is available.

Education Expenditures Indicator

This indicator measures the government’s commitment to investing in education.

Relationship to Growth and Poverty Reduction

While MCC generally strives to measure outcomes rather than inputs, educational outcome indicators can be very slow to adjust to policy changes, and adequate data on educational quality do not yet exist in a consistent manner across a large number of countries. Therefore, the Education Expenditures indicator is used to gauge the extent to which governments are currently making investments in the education of their citizens. Research shows that, for given levels of quality, well-managed and well-executed government spending on education can improve educational attainment and increase economic growth.33 There is also evidence that the returns to education to an economy as a whole are larger than the private returns.34 Investments in basic education are also critical to poverty reduction.35 Research shows that regions that begin with higher levels of education generally see a larger poverty impact of economic growth.36

Source

The United National Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Institute for Statistics (UIS) is MCC’s source of data, http://www.uis.unesco.org. UIS compiles education expenditure data from official responses to surveys and from reports provided by education authorities in each country. Specifically, MCC uses government expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP (%) from the SDG database. Questions regarding the UIS data may be directed to survey@uis.unesco.org or (514)-343-7752.

Indicator Institution Methodology

UIS attempts to measure total current and capital expenditure on education at every level of administration—central, regional, and local. UIS data generally include subsidies for private education, but not foreign aid for education. UIS data may also exclude spending by religious schools, which plays a significant role in many developing countries.

Government outlays on education include expenditures on services provided to individual pupils and students and expenditures on services provided on a collective basis. For FY25, MCC will use the most recent UNESCO data from 2018 or later.

MCC Methodology

MCC uses the most recent data point in the past six years (since 2018)37

This indicator measures public expenditure on education as a percent of GDP. MCC relies on the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Institute of Statistics as its source. Specifically, MCC uses the indicator named “Government expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP (%).” For FY25, MCC first determines if a country has a value reported by UNESCO in 2018 or later. If so, the most recent data available within those years are used. If a country does not have UNESCO data at any point since 2018, it does not receive an FY25 score.

For UNESCO data, the GDP estimates used in the denominator are provided to UNESCO by the World Bank. As better data become available, UNESCO makes backward revisions to historical data.

In FY24 MCC revised its methodology for this indicator shift from a focus on Primary Education Expenditures to Education Expenditures. As a result, the scores from FY24 or later are not comparable to scores from FY23 and earlier.

Girls’ Primary Education Completion Rate Indicator

This indicator measures a government’s commitment to basic education for girls in terms of access, enrollment, and retention. MCC uses this indicator for countries with a GNI per capita below $2,165 only.

Relationship to Growth and Poverty Reduction

Universal basic education is an important determinant of economic growth and poverty reduction. Empirical research consistently shows a strong positive correlation between girls’ primary education and accelerated economic growth, higher wages, increased agricultural yields and labor productivity.38 A large body of literature also shows that increasing a mother’s schooling has a large effect on her child’s health, schooling, and adult productivity, an effect that is more pronounced in poor households.39 By one estimate, providing girls one extra year of education beyond the average can boost eventual wages by 10-20 percent.40 The social benefits of female education are also demonstrated through higher immunization rates, decreased child and maternal mortality, reduced transmission of HIV, fewer cases of domestic violence, greater educational achievement by children, and increased female participation in government.41

Source

UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics (UIS), http://www.uis.unesco.org. Questions regarding this indicator may be directed to survey@uis.unesco.org or +1 (514) 343-7752.

Indicator Institution Methodology