Program Overview

MCC’s $139 million Georgia II Compact (2014-2019) funded the $71 million Improving General Education Quality Project (IGEQ), which aimed to improve the quality of public science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education in grades 7-12. The project invested in rehabilitating education infrastructure and constructing science laboratories in targeted schools. A one-year sequence of training activities was also provided to STEM educators and school directors on a nationwide basis. Download the Georgian translated evaluation brief.Key Findings

School Rehabilitation and the Learning Environment

- School rehabilitation of 91 schools delivered large improvements in classroom walls, ceilings, and floors; installed electrical lighting and central heating; improved classroom temperatures and air quality; upgraded sanitary facilities; and provided new science labs.

- Teachers and students reported that these upgrades substantially improved comfort and safety at school and addressed multiple barriers to classroom learning.

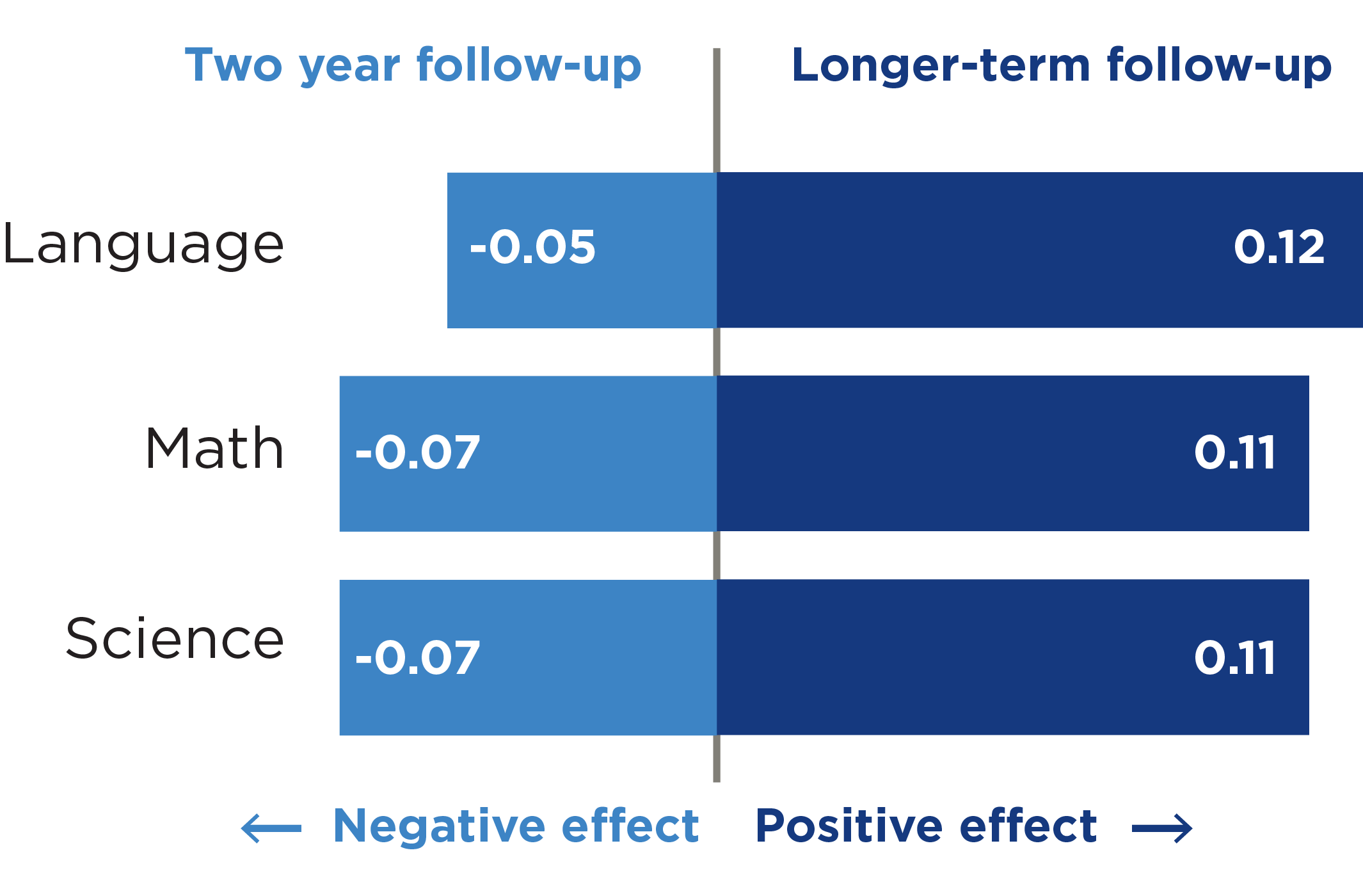

- Impacts on learning outcomes were negative or close to zero for schools in their second follow-up year (in part due to school closures in response to COVID-19), but impacts became positive in schools that were in their third, fourth, or fifth follow-up year.

Educator Training

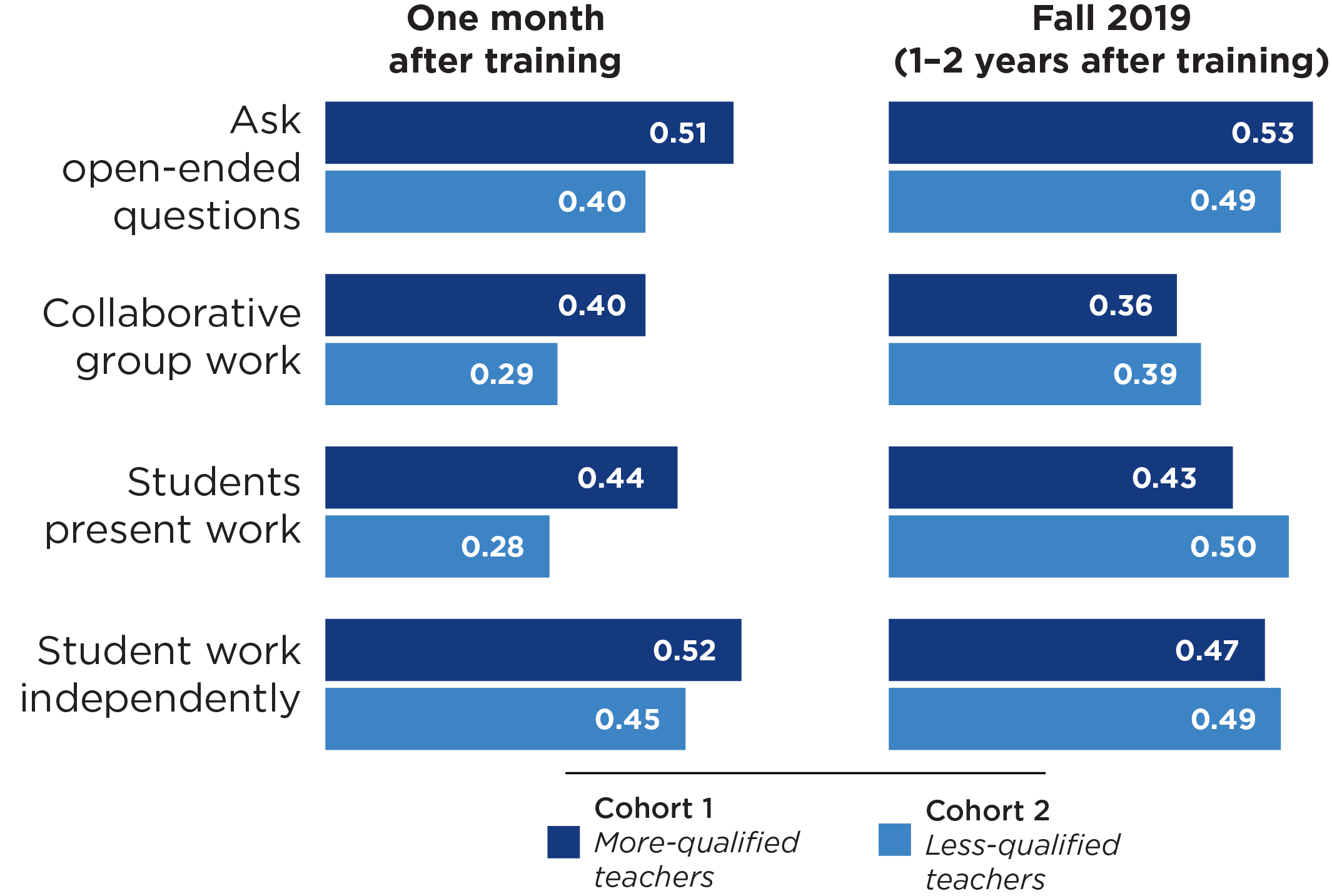

- Two years after training, nearly all teachers have continued to report that they are confident or very confident in having enough knowledge to apply the student-centered instruction practices that were part of the project.

- Practitioner-level teachers (those who had not passed Georgia’s teacher certification exam) also reported large post-training improvements in their use of teaching practices related to students’ critical thinking and collaboration.

Evaluation Questions

This final evaluation was designed to assess the impact of infrastructure and training improvements on STEM education by answering the following questions:- 1 What are the impacts of rehabilitation on the school environment, including temperature, lighting, equipment, and infrastructure maintenance?

- 2 Did rehabilitation impact perceptions of students, parents, teachers, and school directors about school safety, comfort, and the extent to which classroom time is used effectively for learning?

- 3 What were the impacts of school rehabilitation on student attendance, enrollment, dropout and retention rates; time spent studying in and out of school; and learning outcomes?

- 4 To what extent do teachers perceive that their pedagogical and classroom management practices have changed one and two years after the training intervention?

- 5 Did teacher training modules improve teachers’ knowledge of and willingness to use practices related to student-centered instruction, formative assessments, and improved classroom management?

Detailed Findings

The findings of the final evaluation report build upon the interim evaluation report results published in 2019.School Rehabilitation and the Learning Environment

A classroom after rehabilitation

While rehabilitation did not impact student absenteeism or dropout rates, teachers and students consistently reported that these upgrades made it possible to focus more fully on instruction without the distractions present before rehabilitation. Data revealed improvements in the ability to focus on learning. In schools that were not rehabilitated (the evaluation’s control group), students pointed out that poor lighting, inadequate heating, harmful air quality, ceiling leaks, and the lack of indoor toilets were all serious problems affecting their ability to learn. None of these problems remained prevalent in rehabilitated schools. However, teachers in rehabilitated schools did report challenges related to accessing upgraded science labs.

Longer-term follow-up showed the activity had a positive effect on test scores in language, math and science

Educator Training

The less-qualified Cohort 2 teachers nearly caught up to or surpassed the more-qualified teachers in Cohort 1, in their use of student-centered practices.

Notably, the less-qualified teachers in the activity’s second training cohort (who initially reported using student-centered practices less often than the more-qualified teachers in the activity’s first training cohort) reported large post-training improvements in their use of teaching practices related to students’ critical thinking and collaboration. One year after training, these teachers effectively caught up with the more-qualified teachers in their use of project-supported instructional practices.

MCC Learning

- It is important to allow time for teachers to become comfortable with new teaching practices and to train enough teachers to create momentum around a community of practice. MCC should consider this approach when setting expectations in the project logic.

- Several Ministry of Education policies helped bolster the perceived effect of the Training Educators for Excellence activity. MCC should design teacher training interventions to align with existing programs and incentives for teachers to fully participate in the program.

- When designing education investments in contexts of relatively low dropout and high graduation rates, it is important to consider all project causal chains that lead to changes in learning. MCC should consider benefits beyond reductions in dropout when improving learning environments.

Evaluation Methods

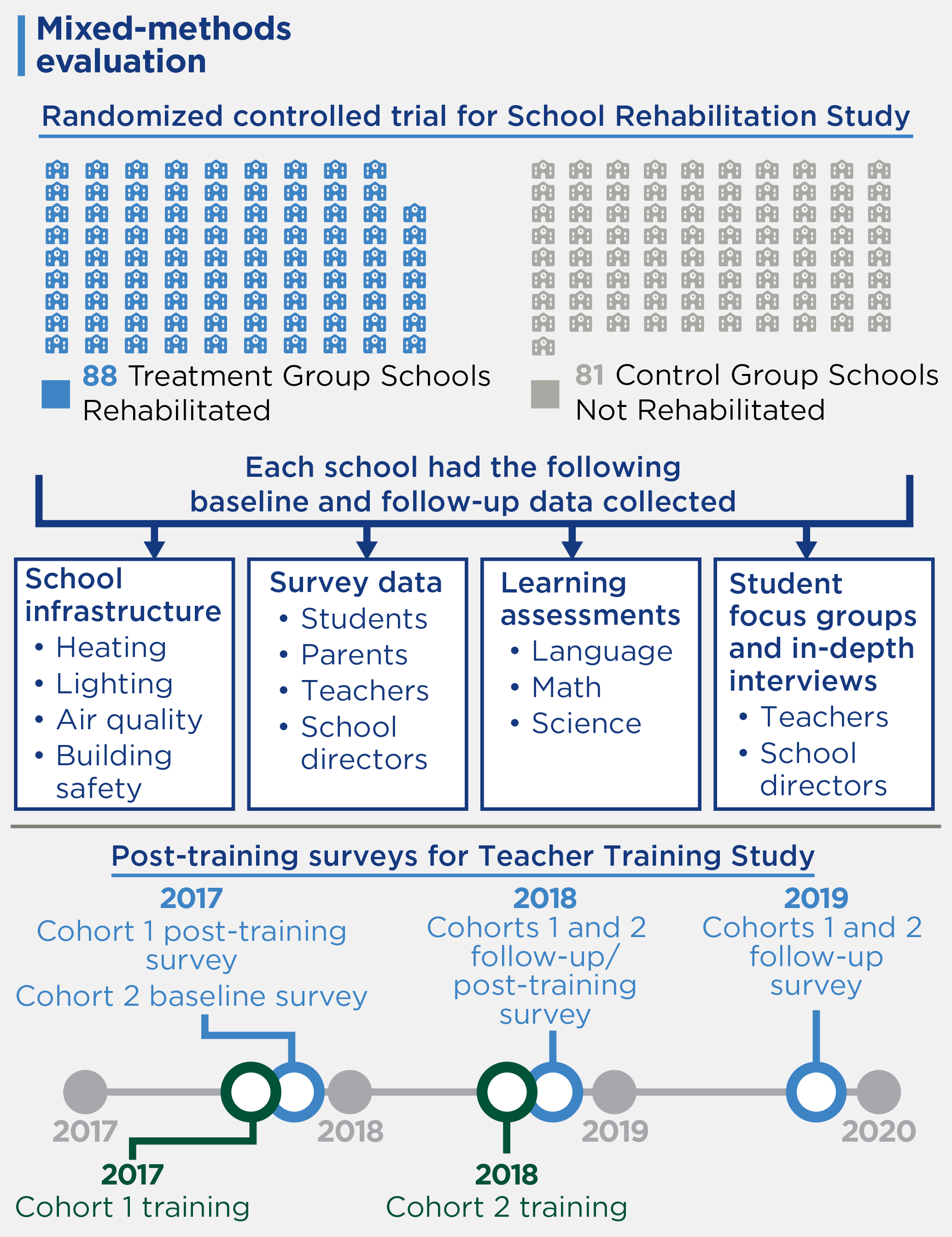

School Rehabilitation Study: The study estimated the impacts of rehabilitation over a follow-up period of up to five years, using a randomized controlled trial design that compared outcomes in 88 of the 91 rehabilitated schools to outcomes in a control group of non-rehabilitated schools. Baseline and follow-up data collection assessed school infrastructure conditions (including direct measurements of heating, lighting, air quality, and building safety) and collected survey data from students, parents, teachers, and school directors. Georgia’s national assessment and examination center also conducted learning assessments in language, math, and science. Finally, the study conducted student focus groups and in-depth interviews with a sample of teachers and school directors to learn more about changes in the learning environment.

Teacher Training Study: The analysis relied on post-training surveys conducted with a nationally representative panel of approximately 1,200 teachers surveyed in 2017, 2018, and 2019. The sample included two separate cohorts of trainees: for the first cohort (more-qualified teachers who completed the training in 2017), the data covers a two-year follow-up period after training; for the second cohort (less-qualified teachers who completed the training in 2018), the data covers a one-year follow-up period after training.

2023-002-2854